Article in Midrasz Magazine, November 2009

In October, 2009, photographs from my Actualities Black & Orange collection were displayed at the Warsaw Museum of Ethnography as part of an exhibition called "Orange Revolutions". I was interviewed in my house earlier in the year, to gather background information for the exhibit.

Midrasz Magazine published an article [in Polish] about the exhibition including this interview. Below is a rough translation of the article, with my additions, using an on-line translator I found on the web. The irony is that I have translated into English a Polish translation of my English interview.

Menachem Kuchar, documentary photographer, orange protester and participant, conversing with Aleksander Czyzewski.

Have you heard of political movements using this colour in the Netherlands, Poland and Ukraine?

I have heard of that in the Ukraine, but not of Poland nor the Netherlands. [As the conversation went on I realised he was talking about the ascension of the House of Orange about which I am familiar.]

Did the protest movement have some sort of standard name, like the revolution in Ukraine?

People just called it the orange campaign.

It was a success in that orange was visible everywhere. Everyone knew what it symbolizes, and likeminded people could easily recognise each other.

From where do you think the opponents of the withdrawal from Jewish settlements [in Gaza] took the idea to decorate cars, clothes, etc, in orange?

A well known journalist [Adir Zik] who passed away during the campaign and actively campaigned against government policy,

said he was happy that someone had finally taken his advice and chosen orange, the colour most visible on colour television.

However the residents of Gush Katif (located in Gaza, the centre of resistance against the disengagement) claimed that orange was always their theme colour. They used it already 30 years ago, because it was a bright [happy] colour [and Gush Katif was such a happy place to live]. It was not then used specifically because of power of the colour. The Ukraine was different. There [I believe] it was chosen to represent the political opposition because of the way the colour stands out [on television].

When did you see the orange mark for the first time?

Exactly one year before the expulsion of the settlers. Protesters created a human chain from Gush Katif until the Wailing Wall [sic].

From then orange became the official colour of the protest movement, despite the fact that all the elements of the orange costume had not yet been developed. Orange was soon visible everywhere. The most popular manifestations were orange plastic bracelets and car stickers.

People also decked their houses and cars with orange ribbons and flags. If people flew an Israeli flag, they added an orange ribbon to it. Orange ribbons flew from car antennae. During the year of protest the whole country was literally covered in orange.

There were some counter demonstrations. The Left started to tie blue ribbons to their cars. By this they wanted to show that they supported Israel, accompanied by a willingness to cede territories. Then some [Orange] people began displaying blue and orange elements together, to demonstrate an [overall] love for Israel, not just for Gush Katif but also for Tel Aviv. The blue campaign waned.

Did orange symbolise passive resistance?

Not in the same way as in the Ukraine. But there was passive resistance. People express their opinions, by whatever means

is available at the time.

If someone was a physician and he wore an orange bracelet, her patients would see it [and get the message].

You can protest by doing nothing overtly out of the ordinary.

Even later on, when it was clear that the settlements would be destroyed, this form of passive resistance continued.

But we are Jews, and Jews are not aggressive (laughter) [I assume I laughed at that point in the interview]. This is part of our mentality (contingent upon merchants persecution. Even now, when we have independence, are not be napastliwi in such situations [lost in the translation]). No one wanted civil war, or even the impression of civil war.

Someone told me that at the Hebrew University, people who previously liked to wear orange clothes, no longer did so, since it had become a political statement with which they did not particularly wish to be identified. Thus orange became the unique colour of the opponents to the withdrawal from Gaza.

It is therefore presence orange wrought on such an impression unto the LORD? [I can't understand this translation.]

When all the [protest] action started, I knew that it will be something great and I wanted to be part of it in

an artistic way. I decided to document the events. Since I am photographer, my perception was very acute [I am a good passive observer].

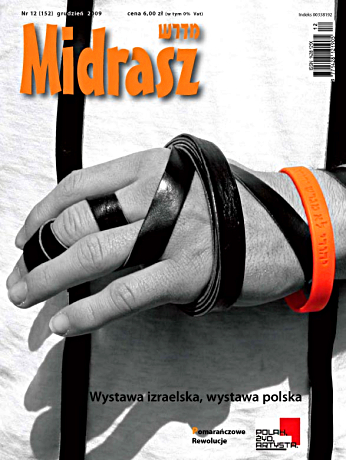

Orange was everywhere. I decided to use black and white photographs showing only the orange colour as my medium. And I went everywhere.

It was also, certainly, visible to the Left. [I'm not sure what the Polish text is really saying, but I said that while I did not follow the orange campaign completely, I carried my camera with me wherever I went and photographed extensively.]

Do you think that this was associated with the orange yellow stars of the Nazi era persecution in Europe?

Some people wanted to use the orange star as part of the campaign,

but the idea was not accepted [a very small number of people did sport an orange star].

I think that people did not want to give the Left an easy argument that converts the whole matter into something radical[? the word here did not translate]. No-one claimed a Holocaust was taking place here, but rather that Gush Katif is an important part Israel, with strategic importance, and that Jews had made their homes there [under government auspices]. In addition to this, an orange star would imply the protestors thought the government to be antisemitic.

Did orange demonstrate resistance with peaceful intentions?

Of course. Peaceful intentions.

What was the protesters reaction to the police and military?

I remember a demonstration, which was completely surrounded by the military.

When time has come for [the afternoon] prayers, a large group of people [demonstators] started to pray together [in a minyan as required by Jewish tradition]. The soldiers joined in the prayers.

I think that the army invested a lot in the mental preparation of the soldiers. When travelling to and from Gush Katif, I would stop and talk to soldiers [along the road]. It was clear that the majority were against the withdrawal. Therefore the army had to really apply itself in the preparation of the soldiers in order to carry out the expulsion.

What was the reaction to your photographs in Israel and abroad?

Positive. More than 500 people attended the exhibition accompanying my book launch.

We sold many books in Israel and in the United States of America. In other countries too, but mainly there.

In the United States reponse has been very positive. In Israel it was too, but not universally. If someone was against the withdrawal, they loved my work;

if they were not, it was not so accepted (laughter). The problem is that I wanted people to appreciate the photographs as [a work of] art, as a document of a social phenomenon and not as [part of] a political campaign.

Did Arab propaganda associate orange with Zionism?

No, not that I noticed.

Efrat, June 2009

Photographs by Menachem Kuchar from his collection Actualities in Black and Ornage are presented at the exhibition Orange Revolutions at the Museum of Ethnographyin Warsaw from 27th October, 2009.

Menachem Kuchar was born in Australia where he completed his formal education.

When he was eight years old, his uncle gave him an old Kodak box camera. He took many pictures over a number of years with this simple device and also dabbled with developing and contact printing. It was only many years later though that Kuchar started to do serious photographic work. He set up a darkroom with friends in Australia and continued to produce diverse photographic work in both black & white and colour until moving to Israel in 1983.

Without a darkroom, Kuchar's photographic output dropped and displays of his work were limited to the walls of his home. Kuchar strongly believes that the camera is only a part of producing the photograph, work in the darkroom constituting a major part the creative process.

With the latest advances in photography, Kuchar has switched to digital cameras and to the digital darkroom. He says the new technology has allowed him to turn the clock back over twenty years, to again produce fine art photography and to further his creative development.

During 2005 Kuchar held two one-man shows. The first of these, entitled "Eating Out in Thailand", was in March at the Little Gallery by the Efrat library. The second, entitled "Actualities in Black and Orange", was in the summer at the Gush Katif Hotel and featured the first photographs in the Black & Orange collection. In January 2006, Kuchar's first book was released. The launch of the book coincided with a one-man show of more than 60 photographs at the Judaica Centre in Gush Etzion.

Kuchar is married to Jillian. Together with their six children, they have lived in Efrat for twenty-five years.

Kuchar currently uses a Canon 5D Mark II camera. Photographs are post processed using the GIMP under Linux.