The Baleng of Bafoussan, Cameroon

An Examination of the Baleng Narrative in Light of Biblical and Rabbinic Sources

Introduction

On a visit to Cameroon in late February 2014, in addition to spending time with the nascent Beth Yeshourun Jewish community, I met with other local judaising groups. These included tribes claiming Israelite or Jewish descent, and others, who while making no claim of Jewish roots, were interested in aspects of Judaism and Noahidism.

One of those claiming Israelite, or perhaps Jewish ancestry, is the Baleng tribe. They live in the mountains on the outskirts of Bafoussan, Cameroon's third largest city. The Baleng are part of the Bamileke ethnic group, each sub-tribe claiming some commonality in their heritage.

The Baleng are governed by a chief. He is surrounded and advised by an inner circle of nine ministers "who help him to rule". The head of this circle is the prime minister, who also acts in place of the chief during any absence.

Our conversation took place in French.

The entrance gate to the Baleng chief's compound |

Accompanied by two members of the emerging Beth Yeshourun community, I met members of the Baleng tribe. Unfortunately the chief was not in the village at the time of our visit, which had been prearranged. We met with the prime minister, a second member of the chief's inner circle and two regular members of the tribe. However we did not obtain as much information as we had hoped as "there are many things to which only the chief is privy". We arranged to subsequently meet the chief in Yaoundé. He was to contact us. Unfortunately this did not take place as of the time of my departure from Cameroon a week later.

We met on the large verandah outside the chief's palatial, though sparsely furnished, house. Within the building was a high vaulted hall including a gallery. The room was capable of seating a few hundred people.

Their Narrative

The Baleng claim to have left Palestine sic (together with all the Bamileke) as a result of religious persecution following the Moslem conquest. This places their existence in Israel subsequent to the destruction of the Second Temple by some six hundred years and of course well after the Judean exile by Bavel and that of the earlier expulsion of Northern Kingdom by Ashur. Accordingly they cannot make a claim to be from one of the Lost Tribes. Their chronicle thus signals that they are from the remnants of the kingdom of Yehuda, those who remained in Israel after most of the Jewish population had already moved on, largely to Europe.

The Bamileke were already a league of sub-tribes at the time they departed Israel. They remain in these original tribal groupings today, all settled in the one region of Cameroon. The Baleng elders emphasised to me that while each of these sub-tribes have similar customs, they were speaking to me exclusively about their particular beliefs and practices.

From Israel, they all travelled south to Egypt, continuing into today's Sudan, south of the Nile's major cataracts. Continuing their southward journey, at each location to which they arrived, they repeatedly met more Moslems. From somewhere in today's Sudan they turned westward, travelling as far as Cameroon. As by this time there was already a Moslem king in Nigeria, they did not continue further west.

Upon their arrival to Cameroon, the tribes conquered the indigenous population, subjugating them to slavery. They told me that today they "continue to subjugate them, though no longer as slaves". I assume as today slavery is illegal in Cameroon.

Later in our conversation they claimed to have left Palestine around 3,000 years ago, contradicting their earlier statement of leaving Israel during the Moslem period. I cannot be sure that they discerned this contradiction. I did not raise the inconsistency. This however would place their departure from Israel during the early years of the united Israelite monarchy. Is it possible that they are unfamiliar with Israel's chronology and believe the Moslem period started 3,000 years ago?

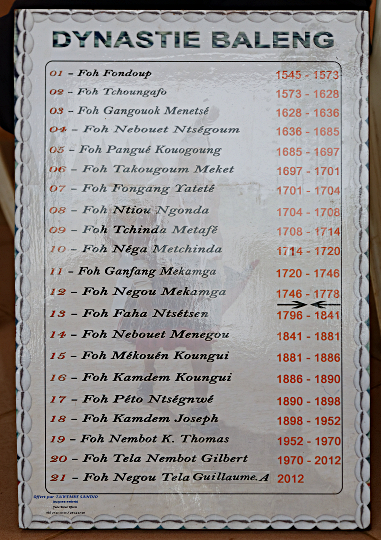

The Baleng's history as a tribe in Cameroon, however, appears only to have commenced in 1545 with the appointment of their first chief. They display a list of the names of their chiefs and the years in which each ruled. This dating leaves a gap of some 700-800 years in their history since leaving Ereẓ Yisrael, assuming they departed in the early Moslem period. This needs to be explained. They did not indicate the duration of their journey from Israel to Cameroon. Perhaps it was hundreds of years.

The Baleng official list of chiefs |

Additionally there is a lacuna of twenty years between two of the listed chiefs. My interlocutors thought this may be related to a time when they had an arrangement with a neighbouring chief, who took the hand of their chief's daughter in marriage. They were very vague on this and it appeared that they really were quite clueless as to what had transpired during those twenty years and how the chiefdom returned to them.

They told us that their history and traditions had been passed orally for many hundreds of years. As a result of this unwritten transmission, they admitted to gaps in their knowledge of their narrative. They told us with great pride that recently they have been filling in these gaps with evidence from archaeological sic and other sources. Unfortunately, in my humble opinion, this casts doubt on many things they told us.

Governance

Succession is always to a son of the chief. As a chief typically has many wives, and subsequently many sons, succession is determined by the inner governing circle, who have undisclosed ways of identifying the true heir from amongst the sons.

If as they told us, that there are many things about the tribe's functioning known only to the chief, it was not clear to me how this secret information is passed on to an heir following his father's demise nor how the inner circle determines the successor.

Religion and Ritual

The Baleng believe in a single god, whom they call Shi. Shi exists everywhere, having no fixed domicile. They do however have specific places that are sanctified and it is from these sites that one can connect with Shi. All of these holy locations are outdoors and each surrounds a specific species of tree. In many faiths, trees are found on hallowed ground. (Cf Asheira. I witnessed a number of these in Uganda. The Tora explicitly forbids trees in the Temple courtyard.) As trees live for generations, being well anchored into the earth, they are seen to provide a level of stability and continuity. This firmness leads to perceived holiness. (Cf the massive structured Banyan tree, Ficus Bengalensis, in Hindu tradition, today India's national tree.)

Even though Shi is omnipresent, individual tribesmen cannot approach him directly. This task is restricted to the priests. An individual, who has a problem which he needs solved sic, informs a priest. The latter then approaches Shi on the petitioner's behalf. The supplicant brings a male goat (it is also permitted to bring a sheep, but never a cow) as an offering. A poor person may bring a chicken. In addition to the animal, the petitioner also offers oil, a cake, salt and some kola nuts. The cake is broken into pieces by the priest who then casts them around the holy area. The oil and salt are used in cooking the meat over an open fire. The kola nuts are eaten with the meat. [Note that all Jerusalem Temple animal offerings were accompanied by meal offerings, prepared in a number of distinct ways, some broken into pieces and always accompanied by oil and frankincense. All animal and meal offerings were salted. They were also accompanied by wine libations.]

Consuming kola nuts is certainly an African tradition. The tree is native to west African rainforests, particularly to Cameroon, Nigeria and Ghana. The nut is caffeine-containing and has a bitter taste. It is a nervous system stimulant and is chewed in many West African countries, in both private and social settings.

|

| |||||||

|

|

||||||||

Close up of sacrificial site. |

For the Baleng, the kola nut is a symbol of peace. Whenever Baleng men meet, chewing kola nuts is considered a good omen for peace. After two men have had an argument, they share some kola, after which "everybody will be happy".

Women are not allowed to approach too close to a holy area but may stand on its periphery. When we later visited a holy site, I asked them to point out where the women would stand. I was surprised as to how non-peripheral was their allowed location. A woman cannot bring an offering, but must rely on a man, usually her husband, to bring it on her behalf. A woman may however inform a priest directly of her problems. [Cf separation of men and women in synagogues, though this segregation only took place in the Temple courtyard during the festival of sukoth.]

Following an offering, all present eat from the meat [cf Sh'lamim offering]. The head and hooves are first separated from the animal and buried. Everything else is roasted and consumed. There is no sprinkling of blood nor burning of animal entrails. The animal is cut open for cooking. Any passerby must stop and join in the feast, remaining until its completion.

Holy sites exist historically. They told us that they no longer remember on what basis these locations were originally selected. They cannot be desanctified. New holy places may be added and consecrated as the village spreads. In order to sanctify a new site, cuttings from trees at an existing sacred site are planted at the new location. While in essence the holiness of a sacrificial site is perpetual, they informed us that this was true "unless government takes them away". I assume there have must have been cases of eminent domain to their detriment. [Cf the expanding of hallowed regions of Yerushalayim, in which certain sacrifices and tithes may be eaten, involved a ritual carried out by Temple priests.]

The older an animal, the better quality the offering is considered to be. Other than this ceremonial approach by the priest to Shi, the Baleng do not appear to have any form of prayer, neither for priests nor for individuals.

Our hosts took us to one of their sacrificial sites. It was in the shade of three huge trees, which were obviously quite old. At the site we saw baskets in which sacrificial animals are brought. However we saw little evidence implying that an offering had been carried out here for some time. There were some signs of scorching at the base of one of the trees, and perhaps on a small patch near the trees. However it did not suggest to me to be a place which had recently been used for open air cooking. It is possible that this was a largely disused site. I do admit that I was a little surprised that they agreed so readily to take us to a holy place, as access to this type of location is often restricted by many religions [cf Temple in Yerushalayim]. The site was quite distant from the chief's compound, though there were a few houses nearby. I assume there are other holy places which are more frequented and closer to the chief's residence.

Birth

Boys are circumcised five days after the baby's umbilical cord falls off. At the same age, both of a girl's ears are pierced. [I was unable to understand a connection between the two procedures other than perhaps some type of equality. At least they do not practice female genital mutilation.] At age twelve months, boys' heads are shaved. Sometime after their tenth birthday, a ritual baptism is performed on boys. They refused to specify what form this takes, whether immersion, sprinkling or other. They told us that even mothers do not know what happens at this ceremony. Other than ear-piercing, they did not inform us of any additional rituals for girls.

Marriage

Marriage is by arrangement between two fathers. Priests are not involved in this process. A dowry, bride price, is paid by the groom's family to that of the wife.

Divorce is strongly discouraged other than in a situation where a man is unable to produce offspring. In such an instance, the new husband must pay the first husband the bride price he had originally paid to the bride's family. The connection between the woman and her original husband is then severed.

Polygyny [one man marrying many women at the same time] is permitted. They burst out laughing at my question as to whether they also allow polyandry [a woman married to more than one husband at a time]. They are a male dominated society.

A female adulterer is banished from the village. On leaving the village boundary, ashes are sprinkled on her.

The Baleng do not practice any menstrual separation.

In the instance of a divorce or perhaps marital breakdown or separation, the divorced woman's children from the subsequent husband are also considered to be the children of the original [childless] husband. However this only has practical application if the mother dies before her second husband. In such a case, the children are forcibly taken from the real father and given to the original husband.

A separated wife is buried along side the original husband.

Mourning

The whole body is buried, sometimes inside the house, but usually outside, nearby. They do not have fixed cemeteries.

Women cannot attend a man's burial.

A tree of peace is planted on a grave.

|

| |||||||

|

| ||||||||

After a few years, the body is exhumed and its head [skull] is separated. It is taken into the deceased's house. Special supplications are recited there, requesting the deceased to intercede with Shi. It was not clear whether a priest is involved in this service, as the entreaties are directed to the deceased and not to Shi. This implies that they believe in some sort of life-after-death. It also shows that they do have some prayers, though in this case at least, not to Shi but to the deceased.

The skull is then buried inside the house. If the floor of the house is tiled, they may not retile the floor above the skull. The remaining body is reinterred in its original grave.

We were shown a receptacle for transporting heads. We actually had to push them to reveal that they performed this exhumation. We had heard about it and wanted to verify it with them. We asked them a number of times until they revealed that this in fact is their custom.

The Baleng have a seven day mourning period. Relatives and people living in same house in which the deceased dwelt, must sit only on the ground for the entire week. They do not cook for themselves during their mourning. Other tribe members bring them food. [Cf Jewish mourning rites.]

Dietary laws

The Baleng do not have any dietary restrictions. Their sacrificial animals are slaughtered with a knife to the throat. While this is also their preferred method for slaughtering non-sacrificial meat, I was under the impression that they are not particularly concerned if it is slaughtered in any other fashion.

They do not eat domestic house animals such as cats and dogs, because they are "too close to us". Otherwise they will eat anything.

Calendar

The Baleng have an eight day week. The eighth day is called pesah. It is a time of total rest. No work at all is performed on this day. It is spent eating with family and in passing on traditions to children. Their seventh day is called l'samba. Some have suggested this is close in sound to the word sabbath or one of its derivatives. There is however no special religious significance to this seventh day.

When I asked them how they managed to live by an eight day week in a country whose legal week was only seven (children must attend school from Monday to Saturday, etc), they responded that indeed today they are unable to practice their pesah, sabbath, any more, though not by choice. I am not sure whether they keep their sabbath any more at all, even when Sunday, the official non-working day, and pesah coincide.

Every second year the Baleng celebrate a three month long festival from December to February. This festival is characterised by much sharing. During this three month period, the priests perform a weekly sacrifice. The year in which the festival occurs is called a "year of grace". The next festival will take place in December 2014, though the "official" announcement is only made 90 days prior to the festival. They do not celebrate any other festivals or special days.

They claim to use a calendar based on a lunar month, but they were unable to explain how this is relevant to anything they do, especially since they base the timing of their three month long festival on the Roman-Christian solar calendar.

Priesthood

Their priesthood is hereditary with some exceptions. If a priest's son is a bad person, he does not inherit the priesthood from his father. [Cf a cohen's son, who is of problematic lineage, loses his hereditary status, though it is retained by the father.] In addition to inherited priesthood, a chief can bequeath priesthood upon anyone whom he deems to be a "good person". This newly designated priesthood is also passed on to future generations.

The priests perform sacrifices wearing special clothes. They are bare-chested and barefoot. They wear a kind of skirt or cloth. No specific colour is required. [Cf cohanim also served barefooted. However we note that many faiths require the removal of shoes when entering a place of ritual or prayer.]

To their consternation, their religion is not recognised by the Cameroon government. As far as the authorities are concerned, they are officially considered to be Christians.

Legal system

The Baleng have their own legal system. Permanent judges are appointed by the chief.

If a dispute cannot be settled successfully, both parties are taken to a special place where "only the truth can be told". If a man lies in this place, something bad will happen to him, possibly even resulting in his death. This potential tragedy will obviate the true situation.

It was not clear to me what their legal system entails nor by what set of laws they judge. However they did tell me that the current chief is trying to appoint legal professionals to the post of judge, e.g. someone who studied law or similar at university. This implies that they do not have any strong legal tradition.

Conversion

Strangers and outsiders are permitted to join the tribe.

Men undergo circumcision (if necessary) in addition to baptism.

Outside women automatically become part of the tribe by marrying a male member.

Customs and language

While they claim that their traditions originated in Palestine, the Baleng [quite honestly and matter-of-factly] concede that things have probably changed over time and geography. They say that neighbouring tribes [the other Bamileke sub-tribes] have similar traditions and customs to theirs, though by now they are not always "the same".

I was unable to substantiate their claims that their language possessed a linguistic similarity to Hebrew. [The neighbouring Nigerian Igbo tribes make similar, though also insupportable claims.] They quoted some words, which they asserted resemble Hebrew. I failed to see a connection in any of their examples. The Bamileke languages belong to the Grassfields branch of the Niger-Congo language family. These are generally classified as Bantoid languages, a division which includes the Bantu languages. This language group is far from Semitic. The various Bamileke sub-tribes speak understandable dialects of the same language.

The Future

When asked if they wish to reconnect with world Jewry or with Israel, they answered very positively. When asked what this meant to them, they responded that only the chief can decide on anything like this. "If the chief says stay here, then we stay here. If he says go to Israel, then we go." Their chief has a great control over their lives.

Analysis and Conclusions

Pro

The Baleng are monotheists. They believe that god is everywhere, though in parallel, there are locations of greater sanctification, where the god is more approachable. This parallels the Jewish concept of haShem's omnipresence, while acknowledging the additional holiness of the Temple in Yerushalayim. They also have a ceremony for creating additional sanctified space as their village grows. This too parallels the procedure outlined in the Talmud for extending the intrinsic holiness of Yerushalayim to its newer suburbs, something which occurred at least twice during the later Second Temple period.

Animal slaughter is [generally] by a blade to the throat.

As in Temple offerings, a poor person may bring fowl if he cannot afford the designated sheep or goat.

Animal sacrifices are accompanied by a meal offering.

They circumcise boys at a young age, which can vary, though is close to the Tora's eight days old.

They circumcise and baptise male converts. This is the Jewish formal conversion ceremony.

They practise a [largely] hereditary priesthood.

Only a priest is permitted to approach Shi. This is true in Tora Judaism in some respects. While each individual, man or woman, is able to communicate directly with God via prayer, since King Sh'lomo's dedication of the First Temple in Yerushalayim, all offerings were limited to the Temple. All sacrificial actions, other than slaughter, could only be performed by a cohen, priest. Two-way communication with God was limited to specially trained prophets and only when in a state of preparedness. Prophecy ceased some time during the early years of the Second Jerusalem Temple.

Their mourning period reflects the Jewish custom of a week, during which time mourners sit on the floor and are not permitted to perform domestic tasks, including cooking.

Con

They possess three narratives as to when they left Israel:

— 3,000 years ago

— some time following the onset of the Moslem period

— at a later time that puts their arrival to Cameroon in 1545

As their timing is based on oral transmission, it is impossible to know whether these various dates are distinguishable to them.

There were too many things which they were unwilling, though more likely were unable due to their admitted lack of knowledge, to disclose to us. They admit to filling gaps in their knowledge of their tradition from modern sources, which are likely to include biases. They similarly concede that things have probably changed over time and geography

Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké (Paris: l'Harmattan, 2010, p. 242) by Dieudonné Toukam corroborates that Bamileke origins can be traced to Egypt and that they migrated to what is now northern Cameroon between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries. In the seventeenth century they migrated further south and then west, to once again avoid being forced to convert to Islam. This demonstrates their claimed aversion to Islam as well as their desire to maintain their traditions, unimpeded by outsiders.

According to the Baleng themselves, their history only appears to have started in 1545 (see photograph above). Accepted local history also relates that the tribes in their region did arrive from the north, fleeing the Moslems as they claim.

The dating in their list of chiefs is interesting in that it uses the Gregorian [Julian] calendar which was only first used in Cameroon during the colonial era, in the 19th century.

The Baleng's description of their observance of shabat is impressive, until you realise that their sabbath occurs only every eighth day rather than every seventh. While eight is possibly more intuitive and practical than seven, as it can be subdivided, it must be doubtful whether any Jewish or Israelite group (which they claim to be) would practise anything other than a shabath every seventh day. They said they were pragmatic about not being able to observe their eighth day sabbath. "The children are at school" and other inconveniences. I said it must be nice that they can keep their sabbath properly every 56 days. My suggestion elicited blank stares.

It is important to take into account their admission that they have forgotten a lot as it was "orally transmitted", especially given that they claim to now be filling in their narrative by researching contemporary sources. This is always one of the fears one has when confronting new claimants. My impression with the Baleng was that this was a sort of admission to playing around with the evidence, most likely unintentionally. The possibility of groups assimilating previously unknown practices and claiming them to be historically their own, is today exacebated due to easy access to previously unknown information via the Internet. In my opinion this possibility must be taken into account. [Cf Falsaha practice before and after Faitlovich]

The fact that the chief retains for himself many secrets, which he does not share even with his inner circle, is also worrying, especially considering that a new chief is only appointed, from potentially a large group, subsequent to the demise of the previous incumbent. In that case one must ask how the chain of tradition is maintained over generations.

Conclusions

Based on my discussions with the Baleng tribesmen, it seems quite uncertain to me that they are of Jewish or Israelite descent as they claim. I arrive to this conclusion, even though they do practise some interesting customs. Their major setback is the fact that they observe an eight day week and that they themselves profess to weaknesses in their oral transmission of their tradition. My regret is that they did not provide us with access to their chief.

Menachem Kuchar, 3rd May, 2014

3rd Iyar, 5775

revised 24th April, 2023