Menachem's Writings

A Partisan Survivor's Letter to His Cousin in Israel

|

This is the first [typed] letter that my late father, Emil Kaufman Kuchar, wrote to his cousin, Ali Breuer, from Topoľčany to Yerushalayim. Ali was two years older than my father, and they were flatmates before Ali went up to Israel in I believe August 1939. He followed his parents and four of his siblings who already arrived during 1938. My father and Ali were born and brought up in Topoľčany. At the time of their births, in 1915 and 1913 respectively, Topoľčany was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It was incorporated into Czechoslovakia in 1919 when that country was created in the wake of World War I. The town is located about 100 kilometres north-east of Bratislava/Pressburg/Pozsony.

It took my father nearly two years to be able to write this letter. His continuing pain and depression are apparent throughout. Though the letter was given to me by Ali in the nineties, not long before his passing, I only recently decided to have it translated from the original German. I have added comments to the letter in italics and inside square brackets to aid the reader in understanding the people and events about which my father writes. |

My father, circa 1946 |

Thank you to my friend, Prof Meir Loewenberg, for providing me with the translation.

Topoľčany, 10th November, 1946

My dear ones.

I read with great joy your letter, dear Alinko, and I was happy to hear that thank God all of you are healthy and together. Regrettably I cannot write anything good about us. From my family I am the only one who survived. With the exception of dear Iren [Iren was my father's oldest sister from a different mother, who had passed away. My grandfather, Bela Barukh Kaufman, subsequently married my grandmother, Fanny Feige Prager. Iren left for the U.S. in 1929. She had one full brother, Isador, whom we will meet soon. My father was the youngest sibling], who as you know, is in America, I am altogether alone and I have no hope that anyone else will return. I am in contact with dear Iren. She sent me immigration documents [affidavit] and she also sends packages.

Since you are interested I will describe exactly the terrible things that happened to us.

| In 1942 when the deportations started [before Shabath haGadol], our dear Isidor, together with thousands of other young men was transported to Poland – from where unfortunately only a very small fraction returned, less than 0.5%. Only those who were expert mechanics, such as Miksa Hochberger and Arika Schenk [I assume these are common friends — I do not know these names] were able to survive as they were needed [by the German army] and therefore were forced to work excessively. In those days there was no help [I'm not sure what he means here re help; I guess that the goyim, who were known antisemites and Catholics, ignored or even were happy with the events]; unfortunately our Boske and Irenke [my father's sisters], as well as all the girls, were deported to Poland. Dear Isidor was murdered already in 1942 and our Boske entered the gas chambers in October 1942. [I don't know how he would know these dates, but the deportations and murders of Slovak Jews occurred very early on. By September 1942, only 618 Jews remained in the town, 20% of the peak population.] The few that remained here [in Topoľčany], on condition that they were essential for the economy [I also heard from my father's contemporaries, that some were also able to remain after paying heavy bribes], were able to save themselves until September 1944 [following the German suppression of the partisan uprising, the first, and until later that year the only for a time, successful revolt against the Nazis. The remaining Jews of Topoľčany were murdered or deported on 8th and 10th September, before the Jews of Bratislava on the day following Yom Kipur, Thursday 28th September. ] |

Ali Breuer and one of my father's sisters. Sadly I don't remember which one. Topoľčany circa 1938 |

In addition there were three work camps: in Topoľčany, Sered and Vyhne that also were maintained until this time. [September 1944. My father's uncle Rav Moshe Prager, wife and daughter, Janka, were in Sered where his uncle, who suffered serious Parkinson's disease, is buried. A non-Jewish, Slovak doctor also incarcerated at the camp, offered my aunt to euthanise him as he would only suffer terribly. My aunt begged him not to do it, but it seems likely he did so. As a result, unlike most, he still merited a Jewish grave.]

If someone did something [against the Slovak law] such as travel without a permit or without a Star of David on his coat, he was immediately sent to a work camp. We [who] worked outside sent food packages to those in the work camps. I was married in 1942, and a beautiful daughter was born to us in 1943. My dear wife was Joli Trauer [whose family was obviously known to Ali].

When the Germans occupied Slovakia, partisan groups were formed here and I joined one of these partisan groups. [I was hoping my father would have expanded on his experiences in the forests, though I understand the trauma that prevented this. However I think Ali was probably not surprised at this statement. He once told that on a particular morning, I guess it was in late 1938, he arrived in shul as usual. However unlike every other day, there was much commotion amongst the congregants. Ali asked his friends what had happened. "A group of brown-shirts was beaten up during the night out in the streets." No-one knew who was responsible, but no-one here in the shul was upset about it; quite the contrary. Then Ali noticed my father was not yet in shul (he was always early to shul, even as I remember him in Sydney). He then recalled that he had heard my father arriving home very, very late that night.]

When the Germans occupied Slovakia they took [away] all of our dear ones. I was with the soldiers in the forests and unfortunately could not do anything. [I don't know how much contact or knowledge they would have had in the forests, but I would guess information moved around.] So it happened that my dear Joli and the child were sent directly to the gas chamber. All women and children under 13 went to the gas chamber – so that none of our women survived.

No one returned from the Gelley family [the family of my grandmother and Ali's mother's oldest sister, Fruma Esther]. Ali and Nazi [Gelley] were murdered by the Gestapo in September 1944. [The Gelleys were the largest horse feed suppliers in Europe, something which the Germans obviously needed, so they maintained them alive in order to keep the supply steady.] Mano [Gelley] did not return from Germany. [He and his family were sent to Bergen-Belsen in November 1944. Mano died of typhus.] Ali [Gelley]'s wife, Miri Friedmann, and Nazi's daughter [short for Ignac], Renika [she lived in Israel. I spoke to her once on the phone], and Mano's wife and three children – all these are here [viz they survived and returned to Topoľčany. I knew them, Rozsi the mother, Zecharia, Vera and Boobie. Zecharia went to England to become a rabbi, later serving a congregation in New York City. He passed away last week. I met him for the first time about 10 years ago. The rest of the family moved to Melbourne where my father was very close to them. I also knew them well.]

I now manage the [Gelley horse feed] business and I will sell it as soon as the title is restored to us because I will not remain here under any circumstances. Neither will the women of the Gelley family remain here. The following are here from the Porges family [a Gelley daughter]: Nacko, Giselka, Piroska, Aliska, Leo and Lajos.

My sister-in-law, Boske, [Isador's wife] survived here in the work camp and returned from Germany since she was deported only at a very late date. [I am confused about 'survived here' and 'returned from Germany'. I would guess she was deported from one of the local work camps to Germany. Perhaps she was in Seged or another local camp and then deported to Bergen-Belsen after September 1944.] Naturally without Walter [her only son]. Our Boske [I assume this is the above-mentioned sister-in-law. My father lost contact with her when they both left Topoľčany. In 1964, he received a letter from her out of the blue from London. She was again a widow by then. After my father's death in 1966 I continued to correspond with her and met her in London in 1974 when I was twenty-one. Sadly she felt she had to apologise to me for having remarried after my uncle did not return, but she told me, "I was all on my own; I had no-one"] has in the meantime married. Also Tyrnau, her husband did not return [I don't know who this is]. Our dear Ali [my father's oldest brother from the same mother] remained in Germany [which I assume means died in Bergen-Belsen. All the oldest sons in the families were named Ali, Avraham, after their grandfather, Rav Avraham Prager, the Rav and Av Beth Din of Topoľčany; he passed away in 1901.].

Unfortunately your [married] sisters are no longer alive. I would love to hear that dear Serenke is with you. At least her. [Three of Ali's sisters remained in Europe; two were married and Serenke was single. The married sisters perished with their families as my father writes here. Serenke survived following great difficulties and made it to Israel. I knew her quite well. She was married and lived in Tel Aviv. Neither she nor Ali had children.]

Concerning my [daily] life I cannot write you much. I work with Nacko Porges in the business. I suffer because the business needs more people and I have to do everything myself. I do not know for whose benefit I work so hard. I am not interested in anything. I have a room near the office but, believe me, I do not have the patience to be alone for more than ten minutes, even though the room is a beautiful room. I do have a radio and an electric record player, but the picture of my dear ones is always in front of my eyes and this gives me no rest. I only live from today to tomorrow. I do not have any friends here. I am always going on trips. Last week I was in Prague [on business], also visiting dear Janka Prager [Gottshall, my father's cousin. Interestingly my mother's sister, Bozsi, was very friendly with Janka at this time in Prague. The two of them plotted to set up my mother with my father, but alas my father at that time intended to marry Miri Freidman.] She told me that you have written to her. [That is why my father does not talk about the fate of the Prager family.]

Please write to me. I promise that next time I will write more, but today I just cannot do so. I myself do not know what I wrote; you have to excuse me but I cannot concentrate when I write these letters, even though everything I write is true. [I think the next correspondence from my father to Ali may have been only in 1948 from Melbourne, Australia. Ali told me that he couldn't believe that my father was there and not here in Israel. The world was topsy-turvy at that time, my father leaving Czechoslovakia and the business in the wake of the communist takeover, taking only whatever he could carry. It is not clear to me why he selected to go to Australia where he had no relatives rather than accept his sister's offer to come to the U.S.]

I was happy to hear that you are married [in Yerushalayim]. I would very much like to see all of you. Please give my regards and kisses to all your dear ones, especially to your dear mother and father. May it be the will of the Almighty that all of you live together in joy for many, many years and that your dear parents experience only joy by living with you. [My father corresponded with his aunt until he passed way in 1966, predeceasing her by about seven years.]

I will end this letter because I can write no more. I greet and kiss all of you.

Yours faithfully,

Emil [signed by hand]

My father's letter really expresses what he wanted to tell his cousin about the war, given his emotional limitations at the time. I wish to add some facts that my father did not write.

Other than to mention in his letter that he joined one of the Slovak partisan groups, which is why he exchanged his German surname, Kaufman, for a Slovak one, my father does not talk about his experiences during this difficult period. I believe he didn't discuss this with anyone, certainly not with my mother. But he did tell another cousin that he had been captured by the Germans and was being led to a firing squad. The Russian army arrived at just the right moment to save his life. He joined them, becoming their barber. He told me that he used to cut their hair by putting a soup plate on their heads and cutting around it. He said they thought him to be quite an accomplished barber.

On 23rd Elul, 11th September, the last sixty-two surviving Jews of Topoľčany were taken by the Nazis to the small neighbouring village of Nemčice where they were forced to dig their own mass grave. They were then shot, to fall into the fresh pit. Only one Jew was left behind in Topoľčany, my grandfather, Bela Barukh Kaufman. He was ninety-one years old and was too decrepit for even the Germans to bother with. When my father returned to Topoľčany, accompanying the front ranks of the westwardly advancing Soviet forces, the townspeople told him that his father had died on 9th October, Sh'mini Atsereth and that they buried him in his backyard. My father never told me how he died — I was 11 or 12 when he related this episode to me — but I am sure he knew. Whether they murdered him, starved him or just neglected him. Because my father exhumed his father and buried him next to his mother, who had died of natural causes in 1940, in the Topoľčany cemetery.

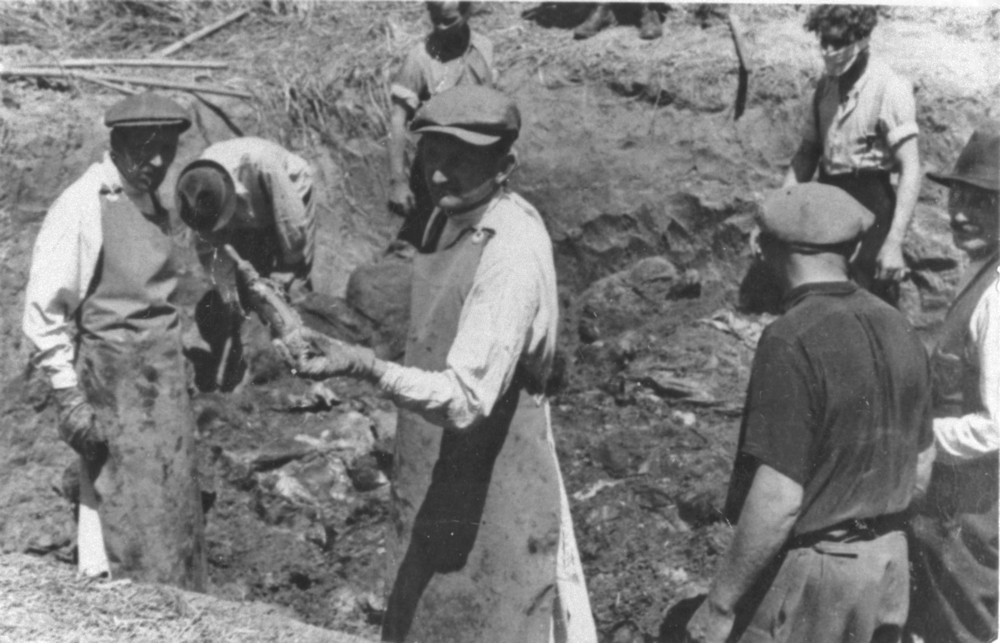

But more than that, my father and some of his few returning comrades exhumed their sixty-two landsmen in Nemčice and brought them to a kever ahim, a mass grave, in the middle of the Topoľčany Jewish cemetery.

My father (centre) and his friends digging up the mass grave in Nemčice |  The reinterred mass grave in the Topoľčany cemetery |

My grandparents' graves in Topoľčany |

Postscript:

Two things I do remember my father telling me which complete all I know about his life from this period. Once we were out in the country somewhere — I would have been eleven or twelve years old. It was a moonless night. Out of the blue my father said, "You know you can see a lit cigarette for miles on a dark night like this". I now believe that was how the Germans captured him.On another occasion, at around the same age he told me, "I will die young, but you will live a long life, like my father". I don't know why a middle-aged man would tell this to his young son. But he died soon-after, at fifty when I thirteen. His father, the last Jew of Topoľčany, died at ninety-one when my father was twenty-nine. Janka told me that my father told her that his heart had been weakened by stress at the firing squad.

I later learnt of another two Jewish survivors in the town. A lady my grandfather's age and her daughter who was looking after her. I have no further information on how they survived.

Posted 28th April, 2018 — 14th Iyar, 5778 — Pesah Sheni

Subsequent to publishing my father's letter here, I have written a number of other pieces about our Partisan:

The Partisan's Trilogy

In addition I have compiled an index of all my shoa related essays.