Reactions to Yom haShoa

and Second Generation Survival Essays

On Yom haShoa in 2017 my daughter, Michal, told me that they had a very interesting talk on her yishuv the previous evening. It was not by a survivor she told me as sadly there weren't too many left. This talk was by a second generation survivor. She asked if I would be interested in doing something like this the following year. I instinctively answered in the negative, but quickly added, "I have written enough on the topic; perhaps I should aggregate all I have written and next year you can share it wth your friends."

Of course I did nothing about it, well not until just before Yom haShoa the following year. I decided to write about the life of a second generationer, namely me. I quite surprised myself at how callous I could be writing on this subject, but it was something that was building up inside me over a number of years, and I suddenly allowed it to explode.

Some background. I grew up in a world that was totally dominated by the shadow of the shoa. My world, my Judaism, my family life — all existed in its shadow. It was inescapable, though much it occurred in non-verbalised conversation, in a language of silence, in secret codes in which we all only knew a part of a larger narrative, a dialogue based on knowledge predicates like "I know", "You know that I know" and "I know that you know that I know", though other than the shared knowledge, no-one could be sure as to exactly what the other knew: my siblings, my parents, their siblings, their inner circle, people in the community.

So I wrote an essay with the intention of publishing it on Yom haShoa, a day to which I never really attached. In my hometown, the day of Yom haShoa was known as Warsaw Ghetto Commemoration Day. Largely the Polish community would gather to remember, to reminisce, to mourn. I didn't attend these assemblies, not until I was involved in Bnei Akiva. You see the Hungarian Jews had another auspicious date on which they would gather at the Hevra Kadisha and do much the same thing; and the Czechoslovakian the same on a third date, each of dates fixed by some local tragedy.

My mother annually religiously attended the latter, as I assume my father probably did during his lifetime. Since my mother was deported with the Hungarians, as a Hungarian which she really wasn't, she could have attended either and show an empathy she would never have for the Polish day.

On Yom haShoa itself, I started morning as any other morning, without too much thought other than to remember to publish my piece when I returned home from the pool, so my essay would visible on my Facebook page for most of the day.

But something happened on this Yom haShoa that changed me.

I'll allow my Facebook page to take over at this point.

On Sunday I wrote a powerful piece on being a 2nd generation survivor. I was going to publish it today.This morning I noticed, perhaps consciously for the first time, that today is called יום השאוה והגבורה, “Martyrs and ‘Heroes’ Day”. I started to think more about the latter. I realised that my late father squarely falls into the heroes category.

From beating up brownshirts in the streets of his town in 1937, to 2 years in the forests fighting the Nazis together with Slovak partisans, my father was the hero I never before was able to acknowledge.

Daddy, אבא! I love you, I miss you everyday. You are a hero, you stood up and you fought.

I’m sorry I never really knew you nor appreciated that for which you stood and fought.

[You see I never before took the word "גבורה" — heroic perhaps — seriously because I always saw it as the left wing zionist excuse for having done close to nothing to assist in the plight of Europe's Jews — not that there was much they could have done other than parachute in a few people in an attempt to contact Jewish undergrounds. However survivors arriving in Israel after the war were very much denigrated and made to feel inadequate for not having taken up arms and fighting the Nazis (see my friend's first person account in The Shattering of the Myth — the Jews of the Disapora and the Jews of Israel). I think the early Israeli parliament, made up largely of the wartime Zionist leadership, had to show itself to be doing something. So they chose a date on which the "Left" did take up arms against their oppressors. It was only years later that Moshe Aren's book, proving conclusively that members of Betar in the Warsaw Ghetto did take an equal share of the heroics and the burdens of the uprising, was published.

It is also worth noting that this date was chosen after the Chief Rabbinate had already assigned asara b'teveth as the day of kadish for those who did not know the dates on which their loved ones were brutally murdered. In other words they had already established a day commemorating the shoa.

[In hindsight I think that the date did turn out to be a good choice as it occurs just a week before Israel's Memorial Day and Independence Day, somehow symbolising the necessity to remember the destruction of European Jewry that would and could not have happened were there a Jewish country at the time.]

Reactions come in quickly. I've protected my correspondents' identities with initials though their names

appear on my Facebook page. Some comments also came in on anonymous email.

"Me" is yours truly's responses and additional comments.

AZ: I also regret I could not get to know my father better. During the war, he was a soldier in the Polish army. He rarely talked about it but I would hear him screaming in his sleep at least once a week when I was growing up. I never thought too much about it, as a child, but now, I really wish I had asked him why he screamed.Me: Just to make it clear, though my father did survive — and only just (see in attached piece) — the war, he didn't come out unscathed. No actually very scarred.

He lost his wife and daughter, father (see in attached piece) 5 brothers and sisters, uncles, aunts, cousins — all brutally murdered.

I wrote something about this some ten years ago. It's on my website at www.menachemkuchar.com

AZ: We all have similar stories. That is why we are all looking forward to the obliteration of Europe.

JL: Menachem Very poignant I would like to talk to you about this as I am going to complete a Master of Philosophy at UNSW on Genocide and i’s impact on the second generation in Australia.

CL: I spent some of my teenage years as a friend of Menachem in Sydney before he made Aliyah. I think I am very lucky indeed that my ancestors all got out of Europe and made their way to Australia in an earlier migration, as soon as the means to travel were available. I feel very blessed for that.

SZ (a cousin from my father's side): Thank you Menachem. So meaningful.

|

A Partisan Survivor's Letter to His Cousin in Israel

Thank you to my friend, Prof Meir Loewenberg, for providing me with the translation. Topoľčany, 10th November, 1946 My dear ones. I read with great joy your letter, dear Alinko, and I was happy to hear that thank God all of you are healthy and together. Regrettably I cannot write anything good about us. From my family I am the only one who survived. With the exception of dear Iren [Iren was my father's oldest sister from a different mother who had passed away. My grandfather, Bela Barukh Kaufman, subsequently married my grandmother, Fanny Feige Prager. Iren left for the U.S. in 1929. She had one full brother, Isador, whom we will meet soon. My father was the youngest sibling], who as you know, is in America, I am altogether alone and I have no hope that anyone else will return. I am in contact with dear Iren. She sent me immigration documents [affidavit] and she also sends packages. Since you are interested I will describe exactly the terrible things that happened to us.

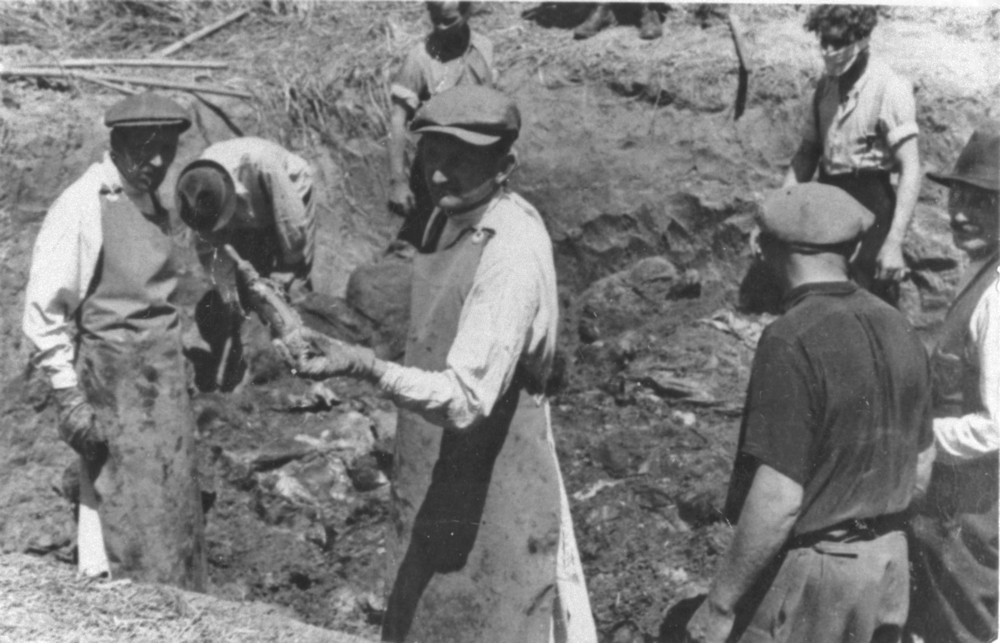

In addition there were three work camps: in Topoľčany, Sered and Vyhne that also were maintained until this time. [September 1944. My father's uncle Rav Moshe Prager, wife and daughter, Janka, were in Sered where his uncle, who suffered serious Parkinson's disease, is buried. A non-Jewish, Slovak doctor also incarcerated at the camp, offered my aunt to euthanise him as he would only suffer terribly. My aunt begged him not to do it, but it seems likely he did so. As a result, unlike most, he still merited a Jewish grave.] If someone did something [against the Slovak law] such as travel without a permit or without a Star of David on his coat, he was immediately sent to a work camp. We [who] worked outside sent food packages to those in the work camps. I was married in 1942, and a beautiful daughter was born to us in 1943. My dear wife was Joli Trauer [whose family was obviously known to Ali]. When the Germans occupied Slovakia, partisan groups were formed here and I joined one of these partisan groups. [I was hoping my father would have expanded on his experiences in the forests, though I understand the trauma that prevented this. However I think Ali was probably not surprised at this statement. He once told that on a particular morning, I guess it was in late 1938, he arrived in shul as usual. However unlike every other day, there was much commotion amongst the congregants. Ali asked his friends what had happened. "A group of brown-shirts was beaten up during the night out in the streets." No-one knew who was responsible, but no-one here in the shul was upset about it; quite the contrary. Then Ali noticed my father was not yet in shul (he was always early to shul, even as I remember him in Sydney). He then recalled that he had heard my father arriving home very, very late that night.] When the Germans occupied Slovakia they took [away] all of our dear ones. I was with the soldiers in the forests and unfortunately could not do anything. [I don't know how much contact or knowledge they would have had in the forests, but I would guess information moved around.] So it happened that my dear Joli and the child were sent directly to the gas chamber. All women and children under 13 went to the gas chamber – so that none of our women survived. No one returned from the Gelley family [the family of my grandmother and Ali's mother's oldest sister, Fruma Esther]. Ali and Nazi [Gelley] were murdered by the Gestapo in September 1944. [The Gelleys were the largest horse feed suppliers in Europe, something which the Germans obviously needed, so they maintained them alive in order to keep the supply steady.] Mano [Gelley] did not return from Germany. [He and his family were sent to Bergen-Belsen in November 1944. Mano died of typhus.] Ali [Gelley]'s wife, Miri Friedmann, and Nazi's daughter [short for Ignac], Renika [she lived in Israel. I spoke to her once on the phone], and Mano's wife and three children – all these are here [viz they survived and returned to Topoľčany. I knew them, Rozsi the mother, Zecharia, Vera and Boobie. Zecharia went to England to become a rabbi, later serving a congregation in New York City. He passed away last week. I met him for the first time about 10 years ago. The rest of the family moved to Melbourne where my father was very close to them. I also knew them well.] I now manage the [Gelley horse feed] business and I will sell it as soon as the title is restored to us because I will not remain here under any circumstances. Neither will the women of the Gelley family remain here. The following are here from the Porges family [a Gelley daughter]: Nacko, Giselka, Piroska, Aliska, Leo and Lajos. My sister-in-law, Boske, [Isador's wife] survived here in the work camp and returned from Germany since she was deported only at a very late date. [I am confused about 'survived here' and 'returned from Germany'. I would guess she was deported from one of the local work camps to Germany. Perhaps she was in Seged or another local camp and then deported to Bergen-Belsen after September 1944.] Naturally without Walter [her only son]. Our Boske [I assume this is the above-mentioned sister-in-law. My father lost contact with her when they both left Topoľčany. In 1964, he received a letter from her out of the blue from London. She was again a widow by then. After my father's death in 1966 I continued to correspond with her and met her in London in 1974 when I was twenty-one. Sadly she felt she had to apologise to me for having remarried after my uncle did not return, but she told me, "I was all on my own; I had no-one"] has in the meantime married. Also Tyrnau, her husband did not return [I don't know who this is]. Our dear Ali [my father's oldest brother from the same mother] remained in Germany [which I assume means died in Bergen-Belsen. All the oldest sons in the families were named Ali, Avraham, after their grandfather, Rav Avraham Prager, the Rav and Av Beth Din of Topoľčany; he passed away in 1901.]. Unfortunately your [married] sisters are no longer alive. I would love to hear that dear Serenke is with you. At least her. [Three of Ali's sisters remained in Europe; two were married and Serenke was single. The married sisters perished with their families as my father writes here. Serenke survived following great difficulties and made it to Israel. I knew her quite well. She was married and lived in Tel Aviv. Neither she nor Ali had children.] Concerning my [daily] life I cannot write you much. I work with Nacko Porges in the business. I suffer because the business needs more people and I have to do everything myself. I do not know for whose benefit I work so hard. I am not interested in anything. I have a room near the office but, believe me, I do not have the patience to be alone for more than ten minutes, even though the room is a beautiful room. I do have a radio and an electric record player, but the picture of my dear ones is always in front of my eyes and this gives me no rest. I only live from today to tomorrow. I do not have any friends here. I am always going on trips. Last week I was in Prague [on business], also visiting dear Janka Prager [Gottshall, my father's cousin. Interestingly my mother's sister, Bozsi, was very friendly with Janka at this time in Prague. The two of them plotted to set up my mother with my father, but alas my father at that time intended to marry Miri Freidman.] She told me that you have written to her. [That is why my father does not talk about the fate of the Prager family.] Please write to me. I promise that next time I will write more, but today I just cannot do so. I myself do not know what I wrote; you have to excuse me but I cannot concentrate when I write these letters, even though everything I write is true. [I think the next correspondence from my father to Ali may have been only in 1948 from Melbourne, Australia. Ali told me that he couldn't believe that my father was there and not here in Israel. The world was topsy-turvy at that time, my father leaving Czechoslovakia and the business in the wake of the communist takeover, taking only whatever he could carry. It is not clear to me why he selected to go to Australia where he had no relatives rather than accept his sister's offer to come to the U.S.] I was happy to hear that you are married [in Yerushalayim]. I would very much like to see all of you. Please give my regards and kisses to all your dear ones, especially to your dear mother and father. May it be the will of the Almighty that all of you live together in joy for many, many years and that your dear parents experience only joy by living with you. [My father corresponded with his aunt until he passed way in 1966, predeceasing her by about seven years.] I will end this letter because I can write no more. I greet and kiss all of you. Yours faithfully, Emil [signed by hand] My father's letter really expresses what he wanted to tell his cousin about the war, given his emotional limitations at the time. I wish to add some facts that my father did not write. Other than to mention in his letter that he joined one of the Slovak partisan groups, which is why he exchanged his German surname, Kaufman, for a Slovak one, my father does not talk about his experiences during this difficult period. I believe he didn't discuss this with anyone, certainly not with my mother. But he did tell another cousin that he had been captured by the Germans and was being led to a firing squad. The Russian army arrived at just the right moment to save his life. He joined them, becoming their barber. He told me that he used to cut their hair by putting a soup plate on their heads and cutting around it. He said they thought him to be quite an accomplished barber. On 23rd Elul, 11th September, the last sixty-two surviving Jews of Topoľčany were taken by the Nazis to the small neighbouring village of Nemčice where they were forced to dig their own mass grave. They were then shot, to fall into the fresh pit. Only one Jew was left behind in Topoľčany, my grandfather, Bela Barukh Kaufman. He was ninety-one years old and was too decrepit for even the Germans to bother with. When my father returned to Topoľčany, accompanying the front ranks of the westwardly advancing Soviet forces, the townspeople told him that his father had died on 9th October, Sh'mini Atsereth and that they buried him in his backyard. My father never told me how he died — I was 11 or 12 when he related this episode to me — but I am sure he knew. Whether they murdered him, starved him or just neglected him. Because my father exhumed his father and buried him next to his mother, who had died of natural causes in 1940, in the Topoľčany Jewish cemetery. But more than that, my father and some of his few returning comrades exhumed their sixty-two landsmen in Nemčice and brought them to a kever ahim, a mass grave, in the middle of the Topoľčany cemetery.

Postscript: Two things I do remember my father telling me which complete all I know about his life from this period. Once we were out in the country somewhere — I would have been eleven or twelve years old. It was a moonless night. Out of the blue my father said, "You know you can see a lit cigarette for miles on a dark night like this". I now believe that was how the Germans captured him. Posted 28th April, 2018 — 14th Iyar, 5778 — Pesah Sheni |

Reactions after posting the letter on my Facebook wall.

HN: Menachem, I have always expressed my joy of your writing. Tonight I have tears rolling down my eyes after reading this very important letter that all should read. You have to translate this to Hebrew. Thank you once again, allowing me and others to be part of your life.Me: Thank you HN. I don't know if you remember my father at all. You and I became friends not too long before he passed away [in 1966].

HN: Shul is where we met in 63 with my first time in Coogee when the congregation was a mixture of Shul and Synagogue. The mixture of the people was amazing. Those that had lost and those that knew what was lost. This is where I met your Father and unfortunately that is where it stopped.

Me: Yes. That's what I write in my 2nd generation essay. I think until you guys came along there was only Mr Silver who didn't have a European accent. Then your uncle and your parents.

HN: Was a big difference from Newtown [shul] and even more so than Central.

Me: Yes, that's for sure. Those, plus the Great Synagogue, were the prewar, pre-shoa synagogues.

PV: I fondly remember your father. He used to teach us to daven after we came home from shule on Shabbat. In particular I remember how he not only taught us to read the Kiddush , however as we would read each sentence in Ivrit, he would then translate it to us in English for us to repeat. Your father wanted to make sure that we did not just say words with our mouth, but also that we should understand and love what we were saying........he would repeat to us the words in the Shema that we should love G-d with all our heart, all our might and all our soul. For the generation of our parents who "survived" the Holocaust, who bore the mental and physical scars for the rest of their lives, it was and is almost unbelievable how they were still able to focus on the future generations. Their good deeds live on through the generations that follow. They have reached immortality in that their good deeds live forever. Me: Yes to everything you write. Given his depression and frustrations and losses as expressed in this letter, written almost 2 years after he returned 'home', it is quite amazing that he was able to live what seemed a 'normal' life to us, and that with all the losses that he endured of people he loved, he never blamed God, and as you say so eloquently, very much wanted to perpetuate the Jewish tradition and love with which was brought up and lived until 1941.

Me: There's one thing I distinctly remember in shul, that my father told me and has remained with me until this day, and today oftentimes makes it difficult for me to be shul, or at least most of those around here.

You and I were sitting in the back row, as usual as I'm sure you remember, supposedly praying — we were 10 or 11 — and my father came up to me and said, "What are you doing?" I answered we were 'davening'. He said, "You can't be saying all those words that quickly." I answered that yes, this was true; I was scanning the rows with my eyes. He told me that that was not prayer, that prayer involved saying, enunciating, each and every word.

This message has stayed with me to the extent that every time I open my siddur, I say all the words, each and every one, no matter how much longer it takes. (I often just start earlier than the minyan.)

HN: Is PV the one I knew from shul?

Me: E, P and I lived in the same building, in the same entrance, each on a different floor. It was crazy place, our mother yelling at each other communicating, through windows and the staircase.

We all shared a very close and similar history. Our parents grew up within close proximity of each other in Slovakia. The three of us were inseparable. P and E were with me when my father died.

OLz: Your explanatory comments and additions, as well as the pictures, make this a most meaningful document. Your children should cherish it, if not now, later.

OLm: "...what a tragic life.....why did you wait so long to translate it ?"

Me: I can't answer that, not yet. I've had it for over 20 years. And only had it translated after Yom haShoa this year. It's again part of our second generation survivors' language of silence; it's some kind of protective mechanism which I can't define; it's again the knowing, but not knowing; of not being sure what you really want to know.

And of course I left it far too late, far too late. There is now may be only one person left in the whole world that knew my father. A second cousin. I sent her a copy of the letter to read. I haven't yet heard from her. She is mentioned in the letter.

DK: Well done, can so feel his pain and loss.

Me: Please share this FB thread. This deserves to go viral. There must be a reason this has taken so long coming out.

OLy: Read the translation of your father’s letter ... very harrowing. Also read the comments to your Yom Hashoah [2nd generation survivor] ... some were very interesting.

Me: Yes, I too have been gratified by the response to both my 2nd generation as well as to my father's 1946 letter.

OLx: One of my cousins (from my mother's side): I always said about that generation how amazing that after what they went through, they were able to go ahead and have (apparently) normal lives ... what resilience, determination, willpower ... of course we don’t know about their nightmares…amazing people!

Fascinating story ... I guess this is how you found out about your sister ... I assume now Dennis [my brother] knows as well.

Me: No, but that’s another fascinating story. It all goes back to the second generation thing, secrecy, silence, protection.

When I was leaving for yeshiva in Israel in 1976, I went to take leave from my father’s cousin to whom I was very close. Her husband, a rabbi and survivor who also lost a wife and children in the shoa, said, “You’ll go and study for a year and then you’ll come back and get married" (which I did). But I replied, “My father didn’t marry until he was 35, so what’s the rush?”. He responded, “Yes, but that was his second marriage!” I was floored, unable to respond, and weakly blurted out a “Yes, of course”.

At almost exactly the same time, my brother, who was doing a professional term at Sha'arei Zedek Hospital in Yerushalayim, went to visit cousin Ali, my father’s correspondent in this letter, in Arad. Ali showed my brother an album of photographs from before the war, before he came to live in Israel in 1939. Nonchalantly he says, pointing to a particular photograph, “Here is you father, his wife and their daughter”. It freaked him out! needless to say.

Sadly I didn’t ask Ali for that photograph (which I never saw) when he gave me the letter and the photograph of him with my aunt (which I added to the letter above). I thought I would have plenty of opportunities in the future. I used to visit him (and two of his brothers who lived in Yerushalayim) often. But alas, I think that was the last time we would meet.

Never put anything off. Do it now ... and spend as much time as you can with your family. Cherish every moment.

PS Once I knew more about my father and his family, I asked my mother about my his past. Her response, “I can’t help you, as much as I want to. He never wanted to share his past, even with me."

IP: Menachem, I don't know how your father was able to cope at all after what he went through. And still there are those that say the Shoah never happened.

Me: Yes, reading his depression two years on, certainly begs the question how did they want to continue living amidst all this cruelty.

BS: Menachem, you should know, you need to know that this letter has brought to life all of those relatives and other Jews who died at the hands of those monsters that murdered so many of our families. By speaking of people in the first person you make them real and their experiences part of our personal memory, much more that movies or museums or documentaries could ever do. Thank you so very much for the time you spent making them alive again, may their memory be for a blessing. Would you be kind enough to allow me to share their story with my friends (almost 1,300 to date) and their followers who themselves have at least 100 each (you do the math). This story needs to be shared to enable others to feel their pain, and your sorrow.

Me: Yes, please, most certainly; please share widely. My aim to have this go viral. Everyone has to know that we are dealing with real people, normal everyday people (and not the lies that monster Abbas is spreading).

Me: My father left us 52 years ago, and I never had the opportunity to hear his story personally. I believe he died before he was in the right mindset to tell his story. But he was the kind of guy, given more time, would have spread it. I am only thankful that at least I have this one letter.

OLw: I don't usually go into shabbos crying, but I did this week after reading your father's letter. Very moving.

AR [both of whose parents lost families in the shoa]: S T U N N I N G !!! ובחרת בחיים Against all odds ... HERO !

And you, amazingly, seek all the details ...

In his condition, I don't think I would have had the wherewithal to get up in the morning ... let alone run a business and start again in a land so far away ... Australia ?!?!? וּקְרָאתֶ֥ם דְּר֛וֹר בָּאָ֖רֶץ לְכׇל־יֹשְׁבֶ֑יהָ וְאִ֥ישׁ אֶל־מִשְׁפַּחְתּ֖וֹ תָּשֻֽׁבוּ

OXu: I remember your father at Coogee Shul. He was a good friend of my late husband [HN above's uncle].

It’s amazing to read his letter and learn how hard it was for people in those horrible war days, thank you for publishing it.

Chazak ve amatz ... to you and family"

Me: [A friend, also a second generationer, shared an article with me today: www.indystar.com which is worth reading.]

First, thank you for sharing the Grunwald article. I [Menachem] could easily have penned these lines: "I was scared of the letter," said the son. "I was curious about the letter," he said, "but at the same time afraid, I think, for its sadness."I was also scared of something, I don’t know what. But neither can I explain why. In the end the agony, depression, pain and frustration that my father’s letter expresses ... I can take it now. I can understand it now. Perhaps 20 years ago I could not; I may not have been adequately prepared. Or perhaps there’s a destiny in the letter only appearing now, when mass social media allows it to spread easily. Perhaps this letter is now a resonse to BDS and the likes of Abbas’s holocaust denial. Perhaps I published it only now as counter to these evil forces that are again encompassing us. Please help my father’s letter go viral. Not for me, but for the Jewish people. The world, 73 years years on, needs a strong reminder."

OLt: Menachem, thanks for sharing. What a treasure that letter is. Whatever we have we have to pass on to future generations.OLs: "I appreciated this letter that was sent to me by my son. My mother was born in topolcany in 1921, spent 4 years in Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen etc. She was the sole survivor of her family; yet unbelievably kept her faith. Several years ago I went back to Topolcany to the cemetery where my great grandparents are buried. My grandparents have no grave. I knew the name Gelley from my mother. She married my father in 1947. I born in Bratislava in 1948. We emigrated to the US. Chazan Klein in Topolcany were my father's relatives & several members had survived."

Me: Here are some photographs of the Topoľčany cemetery. My great-grandfather, Rav Avraham Prager, is buried there, in addition to both my grandparents, as I point out in my notes to my father's letter.

OLr: moving letter, excellent commentary. once in lodon i went to a book shop porges. in conversation with the owner i gathered he was jewish. i thought he came from italy, but reading your letter he probably was from slovakia

Me: Thanks. It's hard to know. Jewish surnames moved all around Europe.

EK: I really feel very sad!!

JL: [In response to my adding the postscripts to the original post] Thank you for sharing Menachem I remember similar conversations with my father.

Me: Our similarities, across our 2nd generation ...

A week later, though I had thought to leave my second generation piece for another, I was convinced by kids to publish what I had written.

On my Facebook wall I wrote,

"I didn't post this piece because I preferred on Yom haShoa to focus on my father's heroism. However some asked me to post this as well. It may be a little ego. It's about my generation, second generation survivors.If you identify, please let me know.

|

My name is Menachem Kuchar I am a survivor My name is Menachem Kuchar I am a survivor of the Nazi Holocaust My name is Menachem Kuchar I am a second generation survivor of the Nazi Holocaust Everyone is aware of the suffering and tribulations of those — our parents — who lived through the horrific years, experiencing unspeakable tragedies in Europe, the place Jews mostly believed they had found refuge for over 2,000 years. Families torn apart, 6,000,000 murdered in the most brutal and inhuman ways. How could anyone surviving this experience continue living — survive, the word itself is obscene, but what better description? Words simply are not a powerful enough tool to express the emotions. How could they continue to live, to want to carry on, in this miserable world that so betrayed its humanity? Most survivors saw purpose in their survival. That they walked out on their feet while most stayed behind, ashes. They were spared by whatever, for something. Call it Fate, call it God, call it Destiny — no-one returned from hell unscarred. Everything they touched had changed. Those, not the most broken, tried to return to a normality, to a semblance of their previous lives, lives without parents, grandparents, siblings, children, spouses, neighbours, friends. Some picked up where they left off, but most couldn't. Because their homes were stolen from them, because the locals tried to — and sometimes did — murder them, because an immense trauma impeded any desire to go back to whence they came, because there was no-one nor nothing for whom nor for what to return. To whatever life they re-emerged, they were determined to live it, in every sense of the word. To abandon and discard the past, except in their intense inner thoughts, in their very private space, in their nightmares deep in the darkness. How they reacted behind closed doors we never knew. They never forgot, they never found true release. Scream and howl and cry in the dead of night. As a result we and our parents acted out a pretend game, a charade. They pretended we didn't know there was something different about us and we too pretended that we didn't know. It was all a sham, but it allowed a semblance of normality. That was important. But we all knew it for what it was. Did they really think if they didn't talk about it it never happened, it may vanish? On the other hand, we really did not know, because they never told us. Neither did anyone else. We knew enough to know something. Not everything you know and learn you acquire through your five senses. There's a sixth sense, and even a seventh in your relationship with your parents, a non-tangible perception. You are not consciously cognisant of it nor can you describe it. Even now as I write I am unable to quantify it. But I live it, here and now, even though our parents are no longer with us; I have lived it my entire life. Our real senses also picked things up. The looks they gave each other in certain situations, conversations with their landsman, a special relationship, a camaraderie built on joint experience, culminating in the ultimate of all awesome experiences. They spoke a vocabulary of which we understood only some of the body language. Their friends knew everything, and we, nothing. My father had been dead for ten years before I found out, by mere chance, that I had had a sister! I was twenty-three years old. It was only in my fifties that my mother finally revealed that I was indeed really left-handed and she had forced me to use my right hand, because "in Europe this was a bad omen — it looked weird". Everything was designed to protect us, a shield for our, and their, sanities. Yes, considering, we do appear to be normal, even quite sane. Our attitude to Jews, and to non-Jews too, was different to that of indigenous Jews. I can walk into a room of strangers, everyone hush. I immediately perceive the second generationers in the crowd. They gravitate towards me. A magnetism, a common fear, a shared sinister secret. As a child, only Jews with central European accents were real Jews. The articulation may be Czech, Slovak, Hungarian, Romanian, German, Polish. We had one Englishman in our shul. I thought him a spy, or perhaps lost, but he always returned the following shabath. I was often embarrassed, not for myself, but for my parents when they conversed with native English-speakers. I felt their pain at not being able to express themselves precisely, at being foreigners in their midsts. I would try and cover for them, speak for them. That seemed to cause even more frustration, so I stopped, holding the embarrassment, with my many other private burdens, well inside. Australian-born Jews and the post-Holocaust mixed like water and turpentine. We had our own shuls, our own rabbis, our own social arena, even our own sports; we didn't mix socially. We didn't feel overly at home in their shuls and they were in the main very lost in ours. Our attitude to tradition was very different. We came from generations with a tradition, they from a shallow, short Jewish continuum, a panoply of Jewish traditions that arrived to distant shores. I recognise why we should not have expected them to understand us. They were happy before we came along and changed the rules. We and our parents were polite and courteous in this company, but neither side understood, nor overly cared about the other. Empathy was lacking. There was tension in the air. They never understood me and my generation, not my very real hang-ups and never our Judaism. They never really wanted to. How could they possibly relate to capos? Our parents recognised them, knew them, ignored them, openly snubbed them — to the locals we were all one. All the time we kept alive our secret. Our parents tried to protect us from it and we to protect them. From what? Because they wouldn't let us really know, our situation was worse. One of our biggest challenges was our inability to achieve our parents' expectations. We weren't living our own lives. We were living the lives our parents never had because of the war, the lives of our uncles and aunts and cousins, whose lives were viciously truncated. We had no choice in what we did, where we went. I was supposed to be Beatrice, but alas the chromosomes were confused. As my mother had no Y chromosomic name prepared she selected that of a doctor who appeared on cover of the newspaper. Having a good local name would provide me protection, hide my cursed identity. But she could never pronounce it. (I never checked who this character may have been, but as my mother had resided in the country for just two years with no previous knowledge of English, it is possible I am named after a mass-murderer who just happened to have been a doctor. Now that would be ironic.) At a later date she decided my brother would make a better doctor — she was correct about that — but that I would be a great solicitor. For years that's how she introduced us. Post trauma Europeans thought these were the only portable professions. Portability was important. That's why we all come from families of only one or two children. Each adult can run and hide with one child; two introduces many pitfalls. Responsibility for repopulating the Jewish world was left largely to us, the second generation. We had to be culturally rounded individuals. I learnt ballet, piano, clarinet, swimming, soccer (never rugby or cricket). I wasn't given a choice and I wasn't particularly good at any of them. Why was music acceptable and art beyond the pale? When I informed my mother I had enrolled in engineering, I audibly discerned her palpitations. How could I ever make a living, bring up a family on something so trivial and childish, whatever it was? She didn't know anyone normal who was an engineer ... and then eighteen months later I switched to Computer Science! In 1972 who knew what a computer was? In each and every endeavour we had to excel. I wasn't allowed to be second in anything. I had to be first in the class; I had to swim faster than anyone else; I had to be the best pianist in the group; I couldn't play merely for enjoyment. Achieve, achieve, over-achieve — there was no other game in town. And if we managed to get close to any of their impossible expectations, the level suddenly rose, higher and higher. In essence nothing was attainable. My parents never understood me. I don't think they tried. What I thought and believed was irrelevant to their future and thus to mine. It had to be what they thought, what they wanted. I was living their escaped dreams, fulfilling their lost life. Yeshiva after high school? Out of the question! No-one in our family did that! [Really? My father comes from a rabbinic family. I guess grandpa became chief rabbi and av beth din on knowledge he found at birth.] You've got to get a profession! Become a real man. Then, maybe then ... First stand on your own two feet ... you never know when you may again have to run. Was I being criticised for what I did wrong, badly, imprecisely, illogically? Or was I being criticised for being the me who was me, not their presumed or desired me. In their eyes, there was only room for one me. I agreed, but that me is me! Is that so bad? My mother left God in Auschwitz. She didn't recognise Him any more. She, as opposed to my father, was an active assimilationist, though she couldn't quite break away, not totally. As much as she tried, as much as she believed she wanted to. In the end she did start to return. As much as I rejected the assertion that I was a combination of people about whom I knew very little, glorified martyrs, my slaughtered relatives, in many ways perhaps that is whom I now am. Can I know? Can I know how much their over-the-top expectations formed me into whom I am? I fight it. I want to choose. Am I better for it? or worse or difficult or ... . I never knew them, these martyrs. They were partial narratives of angels. So I could never know whom I was supposed to be. Who does understand me? I am complex, a conglomeration of dreams about many people who no longer are, for whom I substitute. My mother-in-law certainly doesn't know whom I am. She thinks she does, but she's clueless. We can't even laugh at the same jokes. The source of her myopia? She doesn't speak with a central European accent. Our backgrounds are oceans apart. Merely growing up in Sydney did not place us into the same Australian mindset. I can say about my mother too, that she never knew whom I was, the real me. Towards the end of her life we conversed daily, small talk and family history in the main. Was there ever a warm relationship between us? I don't know. I don't possess the analytic tools to measure. I don't believe she ever accepted the real me, the me I wanted to be, the me I wanted her to accept, to get to know, to proudly call her son. She did everything for me, but was she doing it for me, for a me or for herself? For an imagined son who could never exist in the real and cruel world we inhabit? Can I chance a guess at what a parent-son relationship should look like in normal times? from the perspective of a son? from my personal experience and those similar of my contemporaries? Could we ever know? I pray we have been successful in recognising our children for whom they are and not for what we wanted or expected them to be. My name is Menachem Kuchar I am a survivor I am an artist My name is Menachem Kuchar Yakar ... I am an Israeli I am a survivor I am an Israeli — not Ashkenazi, S'faradi, Teimani nor any subgrouping I am a Jew living our ancient ancestral homeland in the Land of Israel My name is Menachem Yakar 12th April, 2018 — 27th Nisan, 5778 — Holocaust Martyrs and Heroes Day |

Again the comments started to come in almost as soon as I finished posting. Facebook is amazing like that for disseminating information.

Robert, reposting my link to the essay: a courageous and revealing article by a good friend Menachem Kuchar with so much in common with me as most of our 2nd generationers who were raised in Australia or anywhere else post ww2.We were both unique as we both married into families who did not experience the holocaust. As many of you know I have been spending much time and energy (obsessed?) into discovering my roots and made it my mission to find my great grandparents graves with much success after my dad's passing 6 years ago as we are a generation who never had grandparents. So if someone were to tell me there is someone from Melbourne or Jerusalem or Baltimore I wouldn't care nearly as much as if they were from the old country and I would run to seek information about our family history.

In any case all of my weird behavior patterns are always explained by my family and friends as typical 2nd generation behavior so that's my excuse. What's yours?

Me: Thanks Robert.

You put it very well, and my only comment, especially to your last sentence, is "YES".

HN: Love you guys

VL: only survivors understand moshe from lodz ghetto malka from czeshtechowa

CM: Very beautiful and very strong. (btw, grew up [in Canada] totally assimilated & ignorant of the Shoah)

Me: Yeah, there's a big Jewish world out there. All that matters now is getting them/US back together and back home.

IP: Menachem, you have shown your soul to the world. The search for self identity is a lifelong task. To many Jews it seemed that G-d died in the ghettos and concentration camps.

Me: IP, revealing my soul to the world is one thing; too many of my friends are in your business ;-) [he's a shrink]However I think is clear my mother differed greatly from my father, and from me, on the topic of "Did God Survive Auschwitz?". I firmly believe he did and is guiding the world today. My question is "How did He survive?" rather than "where was He?"

Though it took me many years, I do understand my mother, though that doesn't mean I agree with her. She was there; I wasn't.

Our parents had a craziness about them. It manifested in many ways, some of which I have outlined in my essay. And we inherited some of theirs as well as 'invented' some of our own.

IP would know better than me, but I think much of this was [is?] to provide ourselves a barrier from a reality we would prefer never happened and by chance we were caught up in it.

SN: I can so identify with what you have written here. I grew up in Australia with the same heavy burden of 2nd generationers. I carry memories of how my parents wrestled with the horrors of what they went through, even though they shielded me from the horrible details until much much later when I became an adult.

Me: Yes. ברוך השם we are all on the way HOME, some sooner some later. But the time has come for us to sort out our histories and continue as one עם and one אומה. This is what I try to allude at the end of my essay.

ML: so generations never forget what so few lived to tell

RP: Very powerful.

EMa: Hey Menachem... Read your post...read it a number times...a very heavy burden you're carrying...l wish you much strength !!

EMb: Outstanding. כל הכבוד

EMc: Menachem, you expressed my feelings so well. Till this day my very best friend doesn't know me. Her Canadian and American relatives did not share my parents' suffering and loss. My Father lost two boys before I was born. Only I could feel his intense love for my children.

Could I ever make up for my parents' loss of spouses, parents siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins etc. It's really only now that I am more mature and wiser that I feel the enormity of their loss. Frequently I wonder 'how on earth could they could be sane?' Sometimes the burden of my loss of extended family is too much. An only child who once had collectivel 19 aunts and uncles, I was jealous of my daughter. She complained that sitting on the lap of her boney grandmother was not pleasant. Oh, how I longed for even one grandparent. To this day I marvel at the strenth that my parents had to allow me to leave their protected environment and move to Israel for two years, or even to visit Europe post high school. That they loved me I have no doubts but did I make up for their loss. I'm sad to admit that I failed miserably. How could I possibly do so? How is what I keep asking myself. How could my father bury his brother? How could my mother part from her sisters and nieces in the selection? I sincerely wish I could do it all over again. I'd be a better daughter, protect them more and love them more. All that anxiety I caused growing up.

My mother said once that when she emerged from the camps, she could never imagine being a grandparent. Now as a grandmother myself, the most precious thing I have to share with my family is my mother's testimonial.

How did you expect them [your parents] to behave? It wasn't their fault anyway — it was the Germans!

EMd: they protected/overprotected me (never had a bike because it’s too dangerous)

EMe: I cried when I read your piece. It so much described my brother (maybe our parents pressured me less because I was a girl). He ended up studying medicine, but dropped out. It wasn't for him. Eventually he married out.

EMf: I do resonate with much of what you described: portable professions, acquisition of knowledge/skills because unlike material things knowledge cannot be taken away from you if have to pick up an run to the next place for safety, the names we were given to protect us" Re names, I think there is a galuth mentality that existed pre the war. E.g. as opposed to Poland and males in Lithuania, all the Jews in our parents’ part of the world had 2 names, one Jewish and one not. They used the latter outside of the shul almost exclusively. (Here is something I wrote on the topic of names 9 years ago: http://menachemkuchar.com/Writings/073.htm) I think that this and the names of our kids is a negation of the galuth. Our kids are: ישראל משה [my father’s name], אלישע מיכל, חוני, מיטל and אביאל. The crazy thing is that the whole world, including my goyish bank manager already in the 70s, called me Menachem, but my mother steadfastly refused, until the end, always insisting, “that’s not the name I gave you” to which I would reply then who called me after your father if not you? She would just repeat her mantra, “ that’s not the name I gave you”. The same with the date I wanted to celebrate my birthday. She would say, “I know the date on which I laboured with you and it's not today!”

OLx: One of my cousins (from my mother's side): I do resonate with much of what you described: portable professions, acquisition of knowledge/skills because unlike material things knowledge cannot be taken away from you if have to pick up and run to the next place for safety, the names we were given to protect us.

Me: Re names, I think there is a galuth mentality that existed pre the war. E.g. as opposed to Poland and males in Lithuania, all the Jews in our parents’ part of the world had 2 names, one Jewish and one not. They used the latter outside of the shul almost exclusively. (Here is something I wrote on the topic of names — specifically my name — 9 years ago: menachemkuchar.com)

I think that this and the names of our kids is a negation of the galuth. Our kids are: ישראל משה [my late father’s name], אלישע מיכל, חוני, מיטל and אביאל. My mother always had huge problems with these names, attempted to anglicise some, and could not pronounce all of them properly.

The crazy thing is that the whole world, including my goyish bank manager already in the 70s, called me Menachem, but my mother steadfastly refused, until the end, always insisting, “that’s not the name I gave you” to which I would reply then who called me after your father if not you? She would just repeat her mantra, “ that’s not the name I gave you”.

The same with the date I wanted to celebrate my birthday. She would say, “I know the date on which I laboured with you and it's not today!”

EMg: There's a considerable amount I can relate to here (including being a natural lefty who was forced to be a righty)......

And on a more serious note, with a sense of relatives all around us that lived on as ghosts....I can relate much more to his hurt/pain than I can to a very sharp bitterness I sense toward his parents..... But I put myself on a shrink's couch for about 4 years plus to try to straighten out my head in my mid-twenties. That really did settle out a lot of issues for me......

Let's have a cup of coffee over it sometime in the near future.....

Thanks for sharing

EMh: What a Special piece!!.....

It could almost have been a "joint effort" — for us all. Some to greater extent than others!

Specific words & thoughts touch so deeply.

Even so many of us - with only one other sibling!

Menachem is differently a very different "boy" who I remember ... but then aren't we all with age?!

EMi: It must have taken a lot of guts to write about your inability to fulfil your parents' expectations; especially when we have internalized those expectations and see ourselves as losers. We cannot all be Renaissance men. We cannot even be winners in one field. We cannot even be successful losers. I know a survivors' daughter who was constantly berated for simply being alive. "Why are you [even] alive?" they would ask her. How can anyone survive that? She is the most "stuck" person I know. They have transferred to us their trauma and their shame for surviving. There is no way our parents could have seen or promoted our individuality. The question is, can we heal ourselves? Can we overcome? Can we lose the guilt and shame? In my opinion, we can, by focusing on our universal vision, which is to my mind, suddenly, closely achievable. That's the only way, I feel. If you have another way, please write more.

Me: Maybe my classmates, Jerry and Harry remember this. It was third class, though possibly fourth but no later ... we had day trip to Fort Denison. As the former penal colony, then the Sydney weather station, is located on an island in Sydney Harbour, Pinchgut, a little more than a kilometre from Circular Quay, the class travelled there by launch after arriving by bus from Coogee.

My mother refused to sign the permission slip, so I was not allowed to go. She felt I would fall of the boat.

Rather than let me stay at home, the school claimed they were responsible for my welfare during school hours, so I sat in the school yard all day until 3:30 pm when the final bell rang. It was an exciting day ... not.

And finally what I promised Michal over a year ago, a list of all the Shoa related essays I have written over the years.

The Partisan's Trilogy

Posted 10th July, 2018 — 28th Tamuz, 5778

You can send comments to Menachem here: