Menachem's Writings

Yom haShoa, 5780

When Elisha reminded me a few days ago that Yom haShoa was approaching, I responded that I didn’t think I would write anything this year, that I’d already written much on the topic and that וְלֹא ָמצָא ִתי“ it’s better to remain silent if you have nothing new or of value to add to the narrative. As we learn in Avoth 1:17, "And I never found anything better for the body than silence — וְלֹא מָצָאתִי לַגּוּף טוֹב אֶלָּא שְׁתִיקָה"

Last night I was moved by a piece by Ruti Eastman where she describes recently finding the father she had not seen since she was three. While he was no longer alive, she now has a brother she never knew or even knew existed. I recently saw a similar story of two sisters who did not know of each other’s existence, one in the UK and one in New Zealand, who are now happily stuck together in corona locked down New Zealand.

Relatives are finding each other, even after decades of separation. I remember in the seventies, the father of a friend receiving a phone call in the middle of night from his brother in the U.S., a brother whom he hadn’t seen since the early forties in Poland, both assuming until that call that the other was dead. Many similar contacts occurred since then, but those relating to the shoa are becoming less and less, as fewer survivors are still amongst us. And even the ranks of our second generation are starting to wane, the oldest are already 74.

In recent years DNA testing has greatly broadened the scope of finding relatives or at least their descendants as in Ruti’s case. Sometimes with embarrassing results. Like the eighty or more siblings, all children of an early American A.I.H. fertility doctor who told his patients in the early eighties that the sperm was donated by doctors and medical students at the local hospital.

As I have written often, I grew up in a world in which our view of the shoa was opaque. We didn’t talk about it directly, almost as if it hadn’t happened, although this was not much more than a decade after it ended. Our parents wanted to move forward, never to look back, except in the quiet of the night when it haunted them. By osmosis from our parents’ reactions to diverse situations, we knew we were different to our surroundings, we knew we were the offspring of tragedy. And we knew never to dare to ask.

Much of my mother’s family survived — seven out of ten siblings — most of their aunts and uncles and many cousins — but not their parents.

But our father was all alone. We’d met of a cousin from New Zealand, another from Melbourne. There were a handful of landsman in Sydney, of different ages but Topoľčany bound them together. Amongst them too were scarce surviving relatives.

My father had a much older sister, who left Czechoslovakia in 1929 for the US, — I have a vague recollection of her once mentioned, but never discussed. A sister from the same father but different mother. I never gave it a second thought.

Then in 1964, my father received a letter from London, from a sister-in-law, a brother’s wife, Boske. She too was all alone, having lost my uncle and son to the shoa and a second husband a few years earlier. My father was ecstatic and a correspondence ensued. I met my aunt in 1974 in London. She was pleasant, very likeable, though the meeting had a melancholy air. I wished I had known her growing up. She passed away a couple of years later. I had been writing to her but suddenly her correspondence ceased.

My father passed away in 1966. It took some time until I found out there was more.

In 1968 I was in Melbourne, following a Bnei Akiva camp. A young girl came up to me after shul and said, “we’re cousins ... my mother wants you to drop by later”. I went. Her mother was the sister of the cousin I remembered visiting from Melbourne. He too was at the house, as well as their mother. My father’s first cousin’s wife! I learnt they had a brother, Zechariah, a well-known rabbi whom I eventually met in 2010. I was a little apprehensive meeting a great rabbi, but I can honestly say we got on so well that I wish I’d made the contact decades earlier. We have regrets in life, but it should not include family.

Through the New Zealand cousin, who by now had moved to Sydney, I learnt a little more. 1976 and I was travelling to Israel to yeshiva. I went to them to say goodbye. “You should look up our cousins there.” Cousins! I was flabbergasted. What cousins? It turns out that my father’s uncle and aunt, my grandmother’s youngest sister and six children (out of eight), were already in Israel before the outbreak of the war. I also learnt, tangentially to the conversation, that my father had previously been married! My mother was his second wife.

During that year I met four of the six, as well as their children. My father’s family was growing!

But the bombshell came when I visited cousin Ali, Avraham, the oldest sibling. He was last to arrive in Israel, in August 1939! He also had been my father’s flatmate. From him I learnt that my father got married after Ali moved out, and that I had had a sister! nearly ten years older than me. Her name may have been Eva. My father wrote in his letter which I only received well after he passed on that, “So it happened that my dear Joli [my father’s wife] and the child were sent directly to the gas chamber. All women and children under 13 went to the gas chamber – so that none of our women survived.”

My question, which will probably never be answered, is do I have more relatives out there? Should I take Ruti’s lead and DNA myself?

My aunt in New York. She was alive after the war. My father’s cousin told me that my father would joke that everyone was receiving cheques from relatives in America, but he was the only one sending money to his sister. Did she ever marry? Did she have children? My guess is that she would today be at a minimum 120 years old! Perhaps a propitious time to make contact with a family she may have had. But surely if we had cousins we would have known. Surely that’s something neither my father nor his cousins would hide!? Do I surmise that she passed away childless in the late forties or fifties?

And how was my father so sure that his wife and also his child were murdered, “went to the gas chamber”? Were there witnesses? Were there records already known in 1946? What if some otherwise brutal, but childless, SS officer promised his wife a pretty blue-eyed baby, and it was my sister he took home?

How did Boske know her son, my cousin, was gassed? What if ... what if?

My father’s letter from beyond the grave, detailing his horror of the shoa.

You will also find links at the end of this piece to all my shoa writings.

Read Ruti’s blog which started this line of thinking.

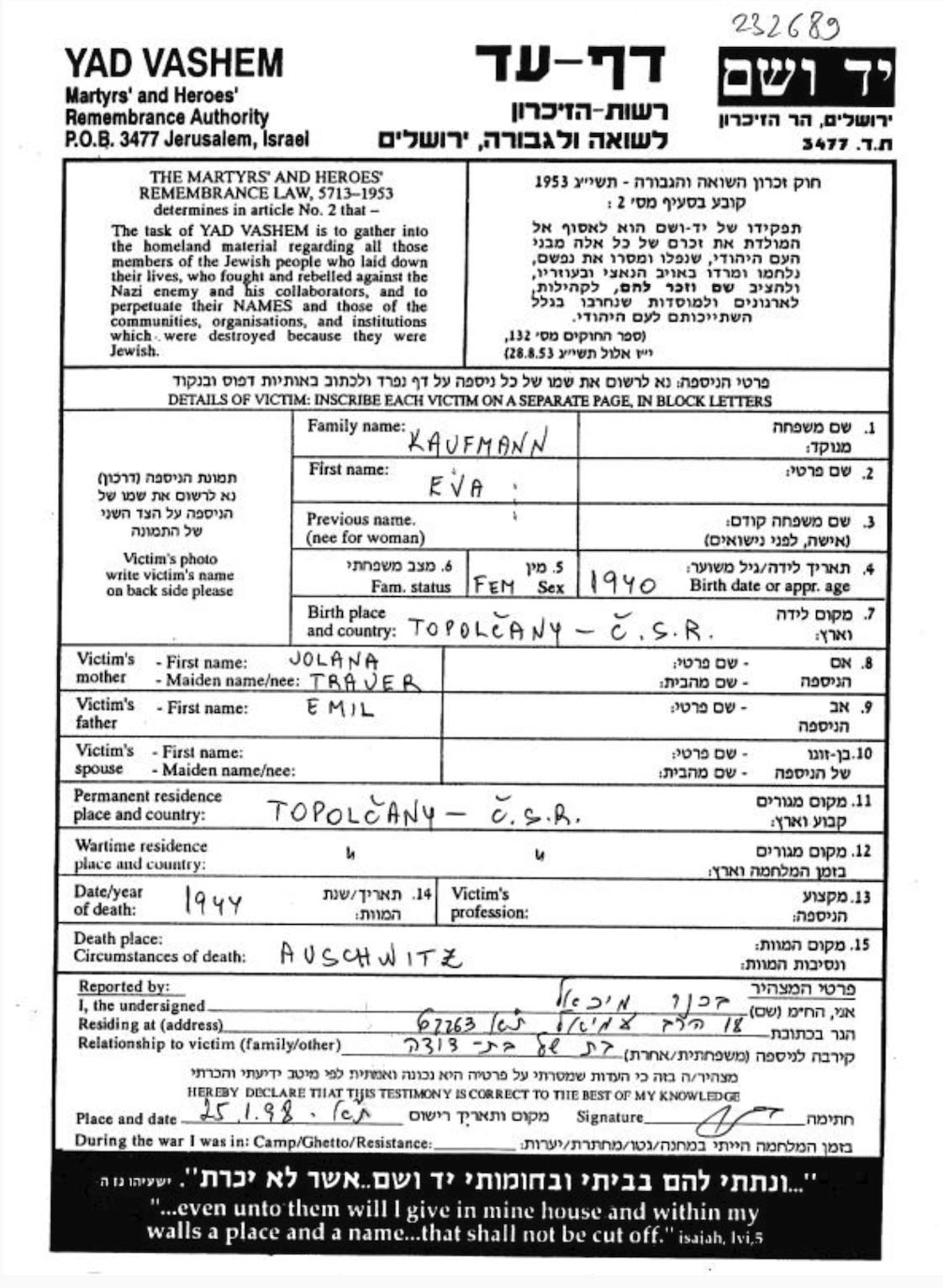

This seems to be my sister’s page on Yad vaShem’s site. However it is inaccurate because, though the parents’ names are correct, the date of birth is not. Other Yad vaShem documents show DOB as 1943 which is what my father wrote in his letter to Ali. Also the report only was in 1998. Yoli Trauer,

I believe Yad vaShem has a big problem with their database because they do not merge/purge it. Eva Kaufmann is listed three times as are my maternal grandparents, a report from my grandfather’s brother, my grandmother’s brother and my uncle their son. Each spelt the surname differently though all are correct: Gluck, Glück and Glueck. All other information is identical.

17th April, 2020 -- 23rd Nisan, 5780