| Menachem's Writings |

|

A Travelogue: Visiting the "New" Jews of Africa

4. Visiting the Abayudaya of Putti

This is part 4 of my East Africa Travelogue. The travelogue is divided into the following sections:

Background

Who are the Abayudaya?

The name Abayudaya in the Buganda language means the "People of Judah", analogous to Children of Israel. The Abayudaya people make no claim to be descended from any Jewish tribe, currently existent or lost, nor are they genetically or historically connected with ethnic Jews. Though lacking historic precedent, the tribe is devout in its Jewish practice. How did this come about?

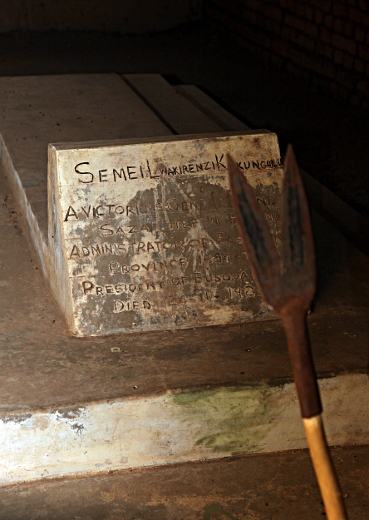

Buganda is a region and former kingdom in eastern Africa, on the northern shore of Lake Victoria. Today this area is part of Uganda, though it was a British protectorate from 1894 until 1962. One of the local leaders at that time was Semei Kakungulu. He was born in 1869 and was converted to Christianity by British missionaries. Today his descendants refer to him as the king of Bukedi, and his grave lists him, amongst other titles, as President of Busoga. I have not been able to ascertain his exact role in Gandan society, but it seems he garnered British support because he commanded a large number of warriors, had connections to the Bugandan court and was a Protestant.

Kakungulu aided the British Crown in conquering large areas of territory, believing that in return for his services he would be appointed governor of the vanquished regions. When the British did not fulfil this perceived agreement, he distanced himself from them, building a house in the beautiful countryside of Gangama on the western slopes of Mount Elgon. In 1913, he became a Melkite Christian, following a practice that combined aspects of Christianity, Judaism and Christian Science. This move further distanced him from the British.

In his semi-retirement Kakungulu began seriously reading the Bible, in Swahili translation. He discovered many contradictions in the texts, eventually becoming convinced that only the five books of Moses, the Pentateuch, the Torah, were true. He rejected the remainder. He was very impressed by the verses at the beginning of chapter 56 of Isaiah,

"Thus says the Lord, 'Keep justice and do righteousness, for My salvation is near, and My favour is to be revealed. Happy is the man that does this, and the son of man that holds fast by it; who keeps the sabbath, not profaning it, and keeps his hand from doing any evil.' Neither let the stranger, who has joined himself to the Lord, say, 'The LORD will surely separate me from His people' . . . ."

He was also critical of the missionaries themselves, claiming that they were misinterpreting the bible by keeping the sabbath on the wrong day of the week. He brought proofs from the new testament accounts of Jesus's death to prove that the day of rest was on Saturday.

| |

| Mount Elgon viewed from the foothills |

When informed by his Christian and Moslem neighbours that the Jews were the only people who accepted only the Torah part of the bible, he responded, "So I'm Jewish". He immediately circumcised himself as did his sons and they commenced observing the Shabbath as he understood it from the texts. Many people followed his actions and moved to live within his proximity. This took place, it seems, in 1917.

We cannot be certain how he "kept the sabbath" with only the written Bible as a source. There are many other aspects of halacha that he could have only guessed at. For example the Torah tells us that Passover is celebrated annually in the "month of the spring". When is that? This is especially difficult when you are located in a region, on the equator, 1,300 metres above sea-level. There is no spring, the only two seasons being wet and dry.

A short time later, in 1920, in what I consider akin to a visit from Elijah the prophet, a man known only as "Yosef" appears on the scene. The Abayudaya claim he came from Israel, but it is more likely that he was a European Jewish merchant passing through the region. Obviously fascinated by the phenomenon before him, he stayed for about six months, teaching the locals many aspects of Judaism including the workings of the Jewish calendar, festival customs, an introduction to kashruth and teaching them to read Hebrew.

Kakungulu set up a "yeshiva" to teach his knowledge of Judaism to his people, combining religious instruction with political leadership. In 1922 he produced a guidebook of rules and prayers for his Jewish community.

| |

| Kakungulu's Grave in Gangama |

Semei Kakungulu died of tetanus in 1928. A division amongst his followers seems to have occured, with some wanting to include belief in Jesus into their core faith.

The leadership role of those who remained faithful to Kakungulu's Judaism passed to Samsom Mugome. He introduced the custom of marriage only within the tribe. He ensured that his daughters, Deborah, Rachel, Naomi and Tamar married men within the tribe. Under his leadership new synagogues were opened in other villages. By the early sixties the tribe had grown to a population of about 3,000 members, living in a number of villages stretching the foothills of Mount Elgon. It seems that under Samsom's leadership members of the tribe started to adopt biblical names. Today they all have biblical names.

In the early sixties Samsom made contact with the Israeli embassy in Kampala, in the hope that some of the members of the tribe would be sent to Israel to study the Torah in depth. This does not seem to have led anywhere.

Tragedy hit the tribe with the accession of Idi Amin to power in 1971. His eight year rule decimated the Abayudaya, his human rights abuses leaving open wounds in Uganda until today. Viewing the tribe as the Jews of Uganda, Amin introduced harsh decrees against any religious practice that was construed even similar to Judaism. He closed all the synagogues, banning outright Jewish prayer. Even the possession of texts written in Hebrew or about Judaism were deemed illegal. Many members of the tribe were forcibly converted to Islam or Christianity to avoid being killed. Those who did continue to pray and practice as Jews did so at great personal risk, in absolute secret. They would go out at night into fields, populated by dangerous wild animals, or into dark caves and other secret locations. By 1979, the end of the Amin era, only about 300 remained faithful to their Judaism. Though Idi Dada was gone, it still took another ten years for Uganda to return to normal. The tribe started to regenerate, building on its youth for its future.

Today the tribe numbers about 1,100 members. In the early 2000's, the American Conservative Movement of Judaism made contact with the tribe. One of the members of the tribe, Gershom Sizomu, was sent to the United States to study rabbinics. He spent five years there, returning with the title of rabbi, though not a great knowledge of Judaism. The Conservatives sent five "rabbis" to the region to convert the tribe to [Conservative] Judaism. This was an unfortunate turn of events, once again unnecessarily dividing the tribe. Some members protested that they had not remained faithful to Kakungulu's teachings for nearly 100 years in order to become not universally accepted Jews. These people separated themselves from the remainder of the tribe, moving to a corner of the village of Putti where they have set themselves up as the She'erit Yisrael community, the "remnants of [Ugandan] Israelites". They practice Judaism as fully as they can, awaiting orthodox conversion. This division has cut across family lines, but fortunately, relations between the two factions have remained cordial.

An Aside

Interestingly, a putto [in Italian] is the representation of a small child, often portrayed innocently naked, heavily used in Renaissance art. Michaelangelo's Sistine Chapel fresco shows many of these figures dispersed amongst the various panels.

The plural of putto is "putti".

These sponsored links arrive via 3rd party feeds. We have no control over their content.

If they interest you, please feel free to click and see -- your interest in these advertisements covers our site expenses.

Our Visit

| |

| Putti Houses |

Enosh, one of the leaders of the Putti community, was waiting for us when we finally arrived at the Mount Elgon Hotel on the eastern outskirts of Mbale. He was keen to get moving. As we had arrived later than expected, we quickly unloaded our luggage and soon were back on the road, with the addition of Enosh in the car.

The ride to Putti takes about twenty minutes, along roads whose condition only worsened further as we drove. We pass the Mbale clock tower, leaving the town in the opposite direction to which we had entered. Our road passes through mainly cornfields dotted with small villages of wigwams and mud bricks, past thin grazing cows. Everything is very green, extremely pastural. The only diversion on the scene was a multi-storied Moslem college just off the main road. This the main campus of the Islamic University in Uganda. This region has been home to Moslems for longer than it has been Christian. Eventually we make a left turn off the "highway" onto a dirt road. A few bumpy miles later we reach Putti.

| |

| The Synagogue in Putti |

The Putti Abayudaya live in a corner of the village which is dominated by Moslems and Christians. I quickly get out of the car to acclimatise. There is neither running water nor electricity here. The houses, surrounding the synagogue, are generally constructed of locally produced mud bricks with corrugated iron or thatched rooves. There is no glass in any of the windows. The only semblance of modernity is that well water is now brought to the surface via a donated solar powered pump. Women -- it seems since biblical times this is one of the roles of village women in agricultural societies -- gather by the well to meet and chat, and more importantly, to fill their containers from the well 'tap' to carry back home, usually on their heads.

Our arrival causes a buzz in the town. Everyone comes out to view the five honoured visitors from Israel. They decide we should all adjourn to the little central synagogue for mincha. This is a great honour, but at the same time presents us with a dilemma. We are the only five "real" Jews here -- I do not intend this to be a racial slur, but rather a halachic statement -- so in essence we do not have a kosher minyan. Our rabbi tries to grapple with the problem. "Ari, maybe you lead the davening."

| |

| Setting up the synagogue in Putti for mincha |

"How does that help", I protest. "He can't say kadish nor kedusha nor the repetition. We're here to see what they do, to observe their Jewishness. Let's ask them to send someone to lead the prayers and we'll just tag along."

The rabbi asks the community, "Would one of you like to lead the services", at which point all eyes turn to Moshe, a bright eyed young man standing nearby.

The synagogue is housed in a single-roomed, thatch roofed building. There is an entrance at the rear of the building, another on the left side, near the front. At the centre of the front wall is an aron kodesh with hand painted dark brown letters aleph to hey on right side of the cupboard double doors, vav to yod on the left. To the left of the aron kodesh the words of the verse shma yisrael are painted in bright blue. The left side of the room is slightly elevated. This is the women's section. Towards the back is another small elevated concrete slab on which sits a reader's table. A new, much large synagogue is under construction next door.

| |

| Ladies section of Putti synagogue |

Moshe dons a talith, ascending the little bima. Men, women and children all take their places in the sanctuary. Moshe opens by reciting the first verse of ashrei, in perfect Hebrew, in a slightly melancholy tone. The entire assembly enthusiastically respond with the following verse, ashrei ha'am sh'kakha lo. Moshe continues the next verse in a slight crescendo.

I am euphoric. Something electrifying is in the air. Here I am, in the middle of deep dark Africa, not a white man in sight, the locals praying with such sincerity that embarrasses me when I think of home, when I think of other diasporas. I push thoughts out of my mind. I desire to savour the moment.

The prayers continue, alternating between Moshe and the congregation crammed into the small synagogue. Moshe becomes more and more elated as we continue chanting the verses of the chapter together. Some of the people are holding prayer books, other seem to know the words by heart.

We arrive at the amida, the silent prayer. The room falls absolutely noiseless. You could hear the drop of the proverbial pin. I was spiritually elswhere, deep in a slow long prayer.

Eventually the prayers end with a resplendent rendition of aleinu, everyone together, out loud.

At the end of this service I look at the rabbi. The rabbi looks at me. Our eyes meet. Then we start simultaneously, with the same words, "I've prayed in many places around the world, but I don't recall many times that I reached the spiritual level I just attained, here, deep in Africa".

| |

| Enosh (left) and Uri addressing us in the Putti synagogue |

The community are keen to meet us, and for us to get to know them. Enosh and his uncle, Uri, the main leaders of the community, come before the assembled congregation. Uri is a grandson of Samsom Mugome. They introduce us to the Abayudaya in general, and then to their key members. Translations are made for those who do not understand English. I'm not sure whether the vernacular here is Swahili or Luganda, but I believe they are similar languages, Swahili containing Arab language elements. The people's love of Judaism exudes in their words and in their voices, and in the eyes of all present, quietly listening to the presentation. They understand that the true manifestation of Judaism is in practice only in the land of Israel, something that many "real" Jews in our generation have yet to understand. They seek spiritual, not material, elevation.

Semei Kakungulu's nephew, now 94 years old, is present. He narrates the history of the tribe including his uncle's and his father's involvement. He relates his experiences during the Amin persecutions, how he continued to practice his Judaism.

| |

| Children's Choir |

Finally Rabbi Riskin addresses the tribe. They sit on every word, often applauding before hearing the translation. The rabbi praises their determination and their perseverance -- and their obvious sincerity. He promises to help them find a solution to their conversion problems. Then he calls upon young Moshe. He offers a flabbergasted young man a full scholarship to come to Israel to learn in his yeshiva. Moshe grabs the rabbi in a hug of elation, his smile reaching from ear to ear. All of Moshe's dreams have come true. Everyone present participates in Moshe's joy.

A choir of children sings a selection of their unique African-Jewish music. Some of the little boys dance unrestrainedly to the rhythm. I brought lollipops from Israel. I hand them out to the children after the performance. They're a big hit.

| |

| Moshe hugging the Rabbi |

We didn't look inside the aron kodesh, but I subsequently found out that it contains a paper Torah, the type children use on Simchat Torah. It was sent to them by a Yeshiva University student who visited about eight years ago and found them reading the Torah from photocopies. Just yesterday I read an article about a Dallas spinal surgeon who volunteers in Uganda, operating on needy children. Last year he made contact with the Putti people, spending shabbath in Putti. He "was saddened to see them take out the paper Torah", so he decided to procure a "real Torah" for them.

| |

| Chicken Delivery Boy and Lollipop Eaters |

Members of the Putti tribe generally do not eat meat, not because they are vegetarians by choice, but rather because they don't know the laws of Jewish ritual slaughter. Ari offers his services as a shochet. They are pleased by the offer, but regrettably inform us that they cannot afford to purchase chickens. They are subsistence farmers, eating what they grow, trading very little. We give them money to buy ten chickens, a feast in their world. After twenty minutes the chickens arrive -- tied in pairs by their legs, each couple slung over the handle bars of the delivery boy's bicycle.

Overall the rabbi is euphoric, deciding on the spur of the moment to return the next day for the morning services. The Putti Abayudaya hold prayer services every morning and evening. There are only two pairs of tefillin for all of them. Even after an orthodox conversion, a lot still will need to be done for these wonderful people. The rabbi, in state of elation, is not oblivious to this.

Personally I felt I had gained an ample picture of life in Putti. We still had a long day ahead of us. The "Conservative" Abayudaya were expecting us. We did not know what to expect there . . . and Enosh was keen to take us Kakungulu's resting place. I decided to spend the next morning photographing in Mbale rather than returning.

It's time to leave Putti. We are convinced of the sincerity and commitment to Judaism of the people we have met. This after all is the reason we came all this way from Israel.

I may have visited a place called Putti, but, I think to myself, I have visited the personification of the putti.

Feel free to view more photographs of the Putti Abayudaya.

Menachem Kuchar, 28th July, 2011

|

Please enter your comments on this article to Menachem:

Previous posts:

- Stories HomePage

- All of my earlier stories

- A Travelogue: Visiting the "New" Jews of Africa -- 1. Arrival to Africa

- Traps for Young Wedding Players -- a short guide to perplexed prospectives

- The End of Days -- The Ultimate Fulfilment of Prophecy

- On Leaven, Sourdough, S'or and Hamets

- A Life Saved by Dog Biscuits

- More on Capos -- A moral dilemma

- The Truth Always Comes Out in the End -- Or does it?

- Remembering my Father on Yet Another Anniversary of His Death -- Yartzeit and Kaddish -- An examination of Death

- The Rise of Fair Consumerism in Israel -- From the perspective of both the buyers and of the sellers -- The saga of a rug purchase

- The Tale of the Sage and His Beadle

- A Search for Meaning in the Expanse -- How significant is a link in a chain?

- The History of My Family via My Grandmother's Candlesticks

- A Short History of Computational Machines via my Israeli eyes

- Our Sages Tell Us Our Name is Engraved on Our Very Souls -- Our name is our very essense

- Ultimately It Boils Down to Greed and Stupidity -- Doesn't it always?

- Capos, Kapos and Nazi Murder Revisited -- How do Holocaust victims, and how should we, relate to Capos?

- On Fasting and Feasting on Tisha b'Av-Transition to the End of Days, the Messianic Era or Let the Festivities Begin

- Guilt by Association -- Facebook conversations with Australian political novices and Hungarian rotten egg eaters -- how many degrees of separation?

- Simulating Reality, Prophecy and Physics Revisited -- "You donít ever want a crisis to go to waste; itís an opportunity to do important things that you would otherwise avoid."

- Today is the 17th Day of Tamuz -- Why do we bother fasting?

- What the Price of Privacy -- Why do we insist on spying on ourselves?

- Who Will Ascend the Mountain of the Lord, Who Will Stand Erect in His Holy Place -- He who has clean hands and a pure heart, who has not sworn in vain against My soul and who has not acted with deceit

- More on Simulating Reality -- Responses and discussion on the original post

- Facebook and Styrofoam -- Man is a Social Creature

- Simulating Reality -- "I, at any rate, am convinced that He does not throw dice"

- Why Do Jews Love a Free Lunch? Anything, Anywhere and with Anyone

- The Present and Future of Communications and Social Media

- The Putrid Parable of the Capped CupCakes A picky porcine person's particularly prickly problematic predicament

- The New World Order via the Prophets of Israel

- The Place of the Holy Temple Today

- The Road from Presov to Kosice. A Mere Sixty Kilometres or an Eternity?

- It's a Matter of How You Say It

- On Matza, Soccer Balls and Red Wine -- How long is a piece of string?

- Woosh, Plump, Ploop, Shhhhh

- On the Psychology of Sex and Wombats

- Stay Away from Bureaucracy. It will swallow you alive

- A Eulogy to my late mother

- The Power of the Web. Finding a manuscript and a family

- Why I Like to Photograph Reflections or Why Do I Always Do Things in Reverse?

- A DisKosher Disdelight. Almost eating out on Broadway

- What Was the Crime of the Sodomites? -- Jingoism, xenophobia or sodomy?

- The more things change, the more they stay the same -- On Babel, the New World Order, One World Government, Carbon Trading and Socialism

- Three Holocaust Experiences: My friends tell me their stories

- "The End is Nigh" -- The clock ticks on -- another step towards Final Redemption

- The History of My Family via My Grandmother's Candlesticks

- I Once Had an Uncle

- Another Uncle and Another, Very Different, Holocaust Experience

- Demographics -- It's Absolutely Not Only About Numbers

- Three Men Spend a Night in a Cold Birmingham Hotel Room

- Swimming with Orders of Nuns and Phyla of Crustaceans

- A Hassidic Story in Real Time

- The Lesbian Rabbi Lied to Me

- All of my Stories

And don't forget to look at my latest (and classic) photographs at www.Menachem.co.il

Enjoy!